The Underground Thomist

Blog

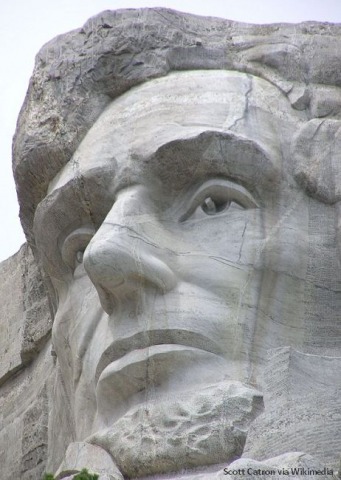

The State of Lincoln’s SoulMonday, 02-27-2023

Query:I write about one of your presidents, Abraham Lincoln. Since I studied the man in the United States, he has become my favorite historical character, barring Christ and some of the saints. Different scholars say different things about Lincoln’s faith. He believed in God, and he read enough scripture to have memorized lots of it. On the other hand he declined to affiliate with any Christian body, and some suggest that he did not believe in an afterlife. I hope he is an uncanonized saint. I place this hope in what seemed to be an authentic conversion when his son Willie died in 1862. I don't know if I am mistaken in admiring a man so hard to pin down. We are supposed to revere virtue, and I see so much in him. He is to me the high water mark of a statesman, up there with St. Thomas More. Here is the kicker: Should I feel this way about Lincoln even though he didn't exhibit in a clear way the virtue of faith? It seems to me that that he embodied the theological virtues far better than some supposedly Christian figures. Is this even possible? I would like to think that if he had been properly catechized, he would have assented, but how could I know? I would love whatever insights you may have on the matter.

Reply:These few thoughts of mine on implicit faith might interest you. But about your question -- It’s true that Lincoln didn’t join any church. Yet we ask God in the Mass, “Remember … all who seek you with a sincere heart. Remember those who have died in the peace of Christ and all the dead whose faith is known to you alone.” At least Lincoln seems to have sought God. We may hope that he was one of those whose faith was known to God alone. If he really did seek God with all his heart, then we can be sure that he found Him, for we are promised that those who seek will find. We just can’t know a person’s inward state. Some who seem virtuous are full of secret corruption, and some whom we might not consider exemplars are striving for God with all their hearts. Yet if God wants us to hope for the salvation of each person, then two things follow: Not only that we should never feel that we are doing something wrong when we do hope for it, but also that we should never feel that we are doing something wrong when we hope that the outward signs of virtue we see in others may be genuine. That would certainly include Lincoln. As you know, the Tradition distinguishes between the ordinary virtues, typified by prudence, justice, temperance, and courage, which we can acquire by human effort, and the theological virtues, typified by faith, hope and charity, which we require the infusion of divine grace. But although the cardinal virtues are insufficient for salvation, they are not for that reason not virtues, and should still be admired. We might add that whether or not he possessed them, Lincoln plainly believed in the theological virtues. He said that we should accept by reason everything in Scripture that we can, and the rest by faith. In his Second Inaugural Address, he also preaches both hope – not just worldly hope, I think, but hope for God’s mercy – and charity for all. Moreover, the Address reflects profound understanding of our need for that mercy. When he writes, “the judgments of the Lord are true and righteous altogether,” he is quoting from Psalm 19, which goes on to plead, “Who can understand his errors? Cleanse thou me from secret faults.” To plead in this way is to concede that we cannot cleanse ourselves. We need to be forgiven and to be purified – two things -- and for both of them we depend utterly on God. That is the crux of the matter, which is another way of saying that it is the Cross of the matter. Despite Lincoln’s profound opposition to slavery, the mob in my country destroys his monuments and pillories his reputation, just because there was slavery. In this world, infamy may be a fate of vice, but defamation is the fate of virtue, and that too is a lesson of the Cross.

|

An Odd Pair of DoubtsMonday, 02-20-2023

“The Argument to a First Cause is very logical,” said the fellow on the bench, “but maybe God is exempt from logic.” I hear this often. But consider: If the Being behind everything doesn’t have to make sense, then nothing has to make sense. It is not a more advanced rationality to demand proof that things make sense; rather faith that things make sense is of the very essence of rationality. “Maybe things don’t have to make sense” is an example of what Chesterton called a “thought that stops thought,” and I think we have to say the same thing about “Maybe God is exempt from logic.” The fellow on the other bench objected to the Argument from Desire, which says that since every natural desire is for something, but we naturally desire something not to be found in this world, that which satisfies this desire must be beyond this world. Enamoured of evolutionary psychology, he said “Maybe we are unsatisfied by the things of this world just because dissatisfaction makes us strive.” And this view is common too. But consider: If there is no God, and the only explanation of our psychology is natural selection, then what are we supposed to be striving for? There is an adaptive advantage in striving for, say, food, but there is no adaptive advantage in striving for something that doesn’t exist. In fact, if the thing we are striving for isn’t real, then why shouldn’t our dissatisfaction with the things of this world merely discourage us from striving for anything whatsoever? There is no point in reaching upward unless there is something up there.

|

Occupied Wall StreetMonday, 02-13-2023

It’s good to see the attention Victor Davis Hanson’s recent commentary “Anarchy, American Style” has been receiving, because most people have not yet caught up with the facts about our new elites. The Occupy Wall Street protesters a decade ago couldn’t have been more oblivious to the state of affairs they thought they were protesting, because Wall Street is already occupied. So are the other centers of power, such as Silicon Valley and Washington, D.C. Social revolutionaries aren’t found in fields and factories any more, but in mansions, town houses, and executive suites. You can’t imagine Mao Zedong in a three-piece suit and wearing Prada? Never mind. Just picture Mark Zuckerberg in a Che Guevara tee. I haven’t much to add to Hanson’s article, except that these are the glory days of smugness and self-admiration. Not that there is a lot of it, because there has always been a lot of it. Today, though, those who wish to pat themselves on the back no longer have to make a choice. In times gone by, the vain and the proud could either glory in self-serving power and privilege, or parade their supposed courage for upsetting the bad old status quo – never both. But now they are the very same people. They have done the impossible. They have squared the circle. They have finally found how to have their cake and eat it.

|

From the Mouths of ChildrenMonday, 02-06-2023

I thrived on the hymns of my Baptist church when I was small. My family was musical, and it seemed natural to listen to the counterpoint and sing in harmony. Thinking that I would love it, my mother put me in the children’s choir. To her great dismay, I rebelled and dropped out. It was unspeakably humiliating to me. I thought we were going to sing things like the Doxology, the way the grownup choir did: “Praise God from whom all blessings flow! Praise Him all creatures here below!” It was wonderful, and contained nothing too difficult for children. Instead we were taught “He’s got the itty bitty babies in his hands,” and I wanted to cringe. The choirmistress was put out with me. Didn’t I know that the great God had the itty bitty babies in his hands? I did know. I believed it fervently. But did we have to sound like itty bitty babies too? The girls seemed to be okay with this, but believe me, it is not the way to encourage boys to be devout. Adults give children the music they like to hear children sing – which can be, but is not necessarily, the music children would like to sing. Or else adults give children bad music to sing, on the assumption that children have no taste. Perhaps they teach them the music they considered jazzy and with-it long ago, when they were in their twenties; I’ll never forget when I heard a troupe of children dutifully singing the schlock praise lyrics, “Lord, you know where I’ve been.” One wondered: Where was that? Perhaps they were all on the rebound from their third marriages and recovering from hangovers. Or had they just been in the cookie jar? Still worse, these days children are often merely accompaniments to taped music. Nobody expects them to sing loudly enough to be heard on their own. And so, of course, they don’t. This is part of the reason why I found it so wonderful to hear two of my grandchildren, a boy and a girl, along with the rest of the new children’s choir at their parish. It was the choir’s first time out. They had been practicing for only weeks, but did they ever belt it out. They did all the liturgical music for the whole Mass, and they did it right. It was wonderful to see their glowing faces. They were getting to do what the grownups did. They were doing it tunefully, reverently, and well. They were serving God. And they loved it. People of different ages need different reminders. When I was a young man, impious, arrogant, full of myself, I needed to hear “unless you turn and become like children, you will never enter the kingdom of heaven.” But when I was eight, desperate to grow up, what I needed to hear was “attain to mature manhood, to the measure of the stature of the fulness of Christ.”

|

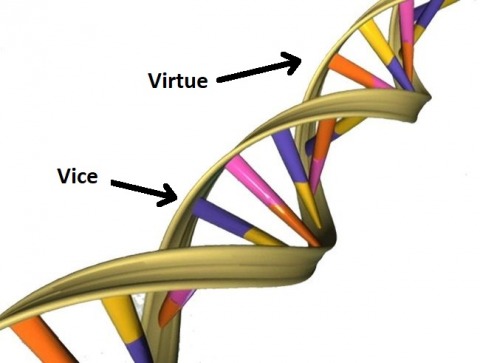

A Genetic Hack for Virtue?Monday, 01-30-2023

** Spoiler Alert ** I recently read Upgrade, a Michael Crichton-style technothriller by Blake Crouch, in which humanity almost comes to an end because someone decides to play God, trying to implement an involuntary, virally transmitted polygenetic hack in order to make the whole human race smarter. What could go wrong? A lot. The first few supergeniuses try to kill each other. The novel is a decent read, and to his credit, Crouch realizes that we don't have an intelligence problem, but a moral problem. Unfortunately, as the plot moves along, he reaches the wrong conclusion: We just need to play God better. For in his view, we do need a genetic hack -- not to upgrade intelligence, but to feel more compassion. What could go wrong? A novel shouldn’t be treated as an ethics treatise, but novels often encapsulate widespread errors. So here, for we do need compassion, but compassion is a virtue. Crouch falls into the sentimentalist fallacy. He thinks it’s a feeling. Virtuous people don’t just feel more of something. The good man feels the right things, for the right reasons, toward the right people, on the right occasions, to the right degree. Feeling so much sympathy that I am unable to punish the convicted mass murderer doesn’t make me compassionate; it makes me a ninny. We need judgment. So even though virtue is habitual, it can’t be programmed – and anything that can be programmed isn’t virtue. Conceivably, a genetic hack might make people have some feelings more intensely. What it can't do is make them more virtuous. It may even make them less.

|

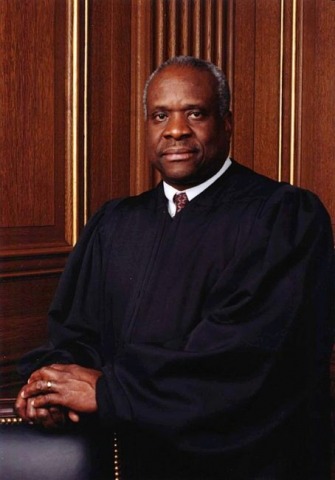

Were They Snowflakes, or Situationalists?Monday, 01-23-2023

This is about being mean. Let me explain. Supreme Court Justices sometimes pose questions about hypothetical situations during oral arguments. Of course, a court does not have the same degree of license to consider hypotheticals in settling a case that a legislature has to consider them in making a law. Still, jurists have to pose some hypothetical questions in order to discern what kind of precedent they are being asked to set. Would they be able to live with it in the future? Carson v. Makin, a case decided in summer 2022, concerned whether a state which offered private school tuition assistance to some parents could deny it to parents who chose private religious schools. After several of the other Justices expressed fears that religious schools are divisive, Justice Thomas posed the following hypothetical question. Well suppose that a school is affiliated with a religious group and they say, “We do infuse our religious beliefs into all aspects of the community, but our salient religious beliefs are that all people are created equal and that nobody should be subjected to any form of invidious discrimination, and that everybody is worthy of respect and should be treated with dignity, and that everybody has an obligation to make contributions to the community and engage in charitable work. Those are our religious beliefs. And we don’t really have any dogma, but these are principles that we think our students should keep in mind consistent with the religious outlook of our community.” Would that school be disqualified? It was a shrewd question. A “Yes” answer would show that fear of divisiveness was a smokescreen – that the state was simply hostile to religion. A “No” answer would show that the state was not hostile to religion, but only to certain religions, on the basis of what they believed. The attorney who was defending the state was clearly uncomfortable. He squirmed. He said that it would be an interesting problem if it ever came up, but that it hadn’t come up. When I had my students read the oral arguments, I thought that they would be annoyed with the attorney for his evasiveness. Answer the question! Some were, but a fair number had the opposite reaction. They thought that just by posing the question in the first place, Justice Thomas was “badgering” the attorney -- that he was being mean to him. Their hostility to hypothetical questions surprised me. What else is one supposed to do in oral arguments? I’ve considered two possible explanations their reaction. No doubt there are others, but these are the two that seem plausible. The first possibility: The snowflake syndrome. As you may have heard, quite a few students these days are extremely uncomfortable with hard, fair give and take. I suppose this kind of conversation is an acquired taste. It used to be acquired in the course of education, but we hardly educate any more. Consequently, these students view being questioned as being “judged,” and they want everyone to hold hands and play nice. This insistence on niceness – as they define niceness -- is pretty exclusionary. It has the rather awful consequence that whatever the dominant view may be, it cannot be challenged. Perhaps, then, the students who were hostile to Justice Thomas’s line of inquiry were reacting along snowflake lines. Justice Thomas’s challenging questions may have seemed “threatening” to them. They might have thought he was practicing “microaggression.” But I don’t think that was it. I lean more toward the second possibility: Situationalism. Perhaps the students who viewed hypothetical questions as “badgering” simply didn’t believe in universal rules. To explain: Ordinarily we say that relevantly similar cases should be treated the same way. If we say “Don’t kill that man – it’s murder, because it’s a deliberate taking of innocent human life,” we are saying that we shouldn’t just hold back from killing that man – we should hold back from any act which fulfills the criteria of murder. Naturally, if you believe in treating relevantly similar cases the same way, you will find that hypothetical questions can often be helpful. I don’t mean silly ones, like “What if the teachers in that school were Martians?” or “What if the students were brains in a vat?” I mean reasonable ones, like “What if the school was associated with a religion which taught Q?”, when there are, in fact, religions which teach Q. But situationalists believe that there are no relevantly similar cases. Every situation is unique. Therefore, when we decide what to do in this situation, what we might do in other situations is irrelevant; to decide is just to decide. All we have to go on is the seat of our pants. In this view, it isn’t just that some rules have exceptions. It’s that all rules have exceptions -- so many exceptions that there is no point in having rules. Of course we could try to do without rules. We could abolish laws and have only judges, sages who decide each case in complete isolation from every other case. The Western tradition has wisely rejected this path. We proclaim “the rule of law, not the rule of men.” Another way to say it is that our tradition is not situationalist – and that not being situationalist is a very good thing. Being a snowflake is a character trait. Believing in situationalism is a philosophical position. I wonder, though, whether there is a relation between them. Snowflakes may be predisposed to believe in situationalism. Situationalists may have a hard time not acting like snowflakes, because the expectation of consistency will seem so unreasonable to them.

|

Politics and Language, RevisitedMonday, 01-16-2023

Roe may have been overturned, but abortion is still with us, and language is endlessly manipulable. In homage to George Orwell, here are a few more words, phrases, and idioms for the Newspeak Dictionary. The long-delayed Eleventh Edition is still in preparation. Reproductive rights. One would think a reproductive right protected the ability to have a child whom other people didn’t want you to have. However, abortion is about being able to do away with a child that other people want to save. Properly speaking, it is an anti-reproductive right. The expression “reproductive rights” is a way to support killing babies, and yet get the good vibes associated with having them. Pro-choice. Abortion is pro-choice in the same sense that the antebellum politicians who wanted the states to be able to allow slavery were pro-choice. It is “pro” a particular choice by particular people. The slave had no choice about enslavement; neither did the people who wanted to free him. The baby has no choice about abortion; neither do the people who want to save him. It’s my body. The Romans used to say something like this too. A father could kill his children at any age because they were considered parts or extensions of his body. Of course, children are parts of us in the sense that we cannot separate our well-being from theirs – but they are not parts of us in the material sense, like fingernails we throw away. Biologically the baby is not a part of the woman’s body, but a separate individual inside her body, entrusted to the closest of all possible care. It's not my business. Pontius Pilate said something similar when he washed his hands before the crowd and said “I am innocent of the blood of this innocent man.” He meant “Don’t blame me – I’m not killing Him – I’m only giving other people the authority to kill him.” We make the same excuse when we authorize abortion. I’m not going to tell anyone else what to do. True, we shouldn’t butt into other people’s personal business. But killing other people isn’t anyone’s personal business, and stopping them from doing so isn’t butting in. By the way, would you say “I’m not going to tell anyone else what to do” if the question were whether parents may kill their newborns? I hope you wouldn’t. But did you know that some people do? In medical ethics, the latest euphemism for infanticide is “after-birth abortion.”

|