The Underground Thomist

Blog

Enough With the Praise Already!Monday, 02-21-2022

A young nonwhite woman in graduate studies – at my university, but not in my department – told me how maddening she found it that none of her teachers or advisors would give her any constructive feedback no matter how she pleaded for it. Everything she did was great, fine, wonderful. It was as though she could do no wrong. Observing that her woke mentors spent more time talking about race and sex than training her in her field, she told me she thought they were patronizing her. I suggested that they may also have been terrified that they would be accused of racism or sexism if they didn’t patronize her. She readily agreed. We both knew that in the wokest circles, each person spends a lot of time nervously looking over his shoulder.

|

Common Good Jurisprudence, Fettered and UnfetteredMonday, 02-14-2022

Various writers including Adrian Vermeule of Harvard have advanced a rather unfettered common-good approach to jurisprudence. Some who like the approach have suggested that it is not much different than what liberal judges have been doing for years – except that it is conservative. To me, vigorous judicial activism seems equally alarming whether it is practiced by the left or the right. Yet we had better not judge hastily, for after all, the purpose of law is the common good. Is there such a thing as a fettered common-good jurisprudence -- a way to have judges consider the common good which puts the brakes on judicial usurpation of legislative judgments of the common good? Some have suggested a relatively modest sort of common-good jurisprudence, which would allow judges to apply the criterion of the common good only when the law is unclear. Maybe, but some questions remain to be asked. Let’s try to think not like lawyers, but like constitutional designers. In the first place, why not say that judges should use the criterion not when the law is unclear, but only when failure to do so would produce a result contrary to presumed legislative intention? Or, to limit judges even further, why not say that they should use it only when failure to do so would produce a result contrary to actual legislative intention? For that matter, if the law is ambiguous, but the situation is not an emergency, then why must judges rule at all? Why not say that no ruling can be made until the legislature clarifies the law? I know this isn’t how we usually think about such matters. But should it be? I am thinking especially of regulatory law. Suppose judges do use the criterion of the common good. May they interpret the common good differently than the legislature does? And how much does the answer to that question depend on how confused about the meaning of the common good the judges -- or legislators -- are in the first place? Someone has to decide how confused they are, of course. I am thinking of the constitutional craftsmen and revisers -- and yes, I know there are problems there too. If we do want judges to use the criterion of the common good, then how can we keep judges from defining the common good tendentiously, tailoring their definitions to suit their personal agendas? We don’t want the incantation “the common good, the common good” to be an abracadabra which allows judges to do whatever they please. By the way, a similar problem arises if judges are allowed to consider the natural law – definitions may be tendentious in that realm too. I’ve written before that this is no reason to say that judges should not consider the natural law. For even if judges push the natural law out the front door, what amounts to careless natural law reasoning creeps in through the back door, disguised as something else. So, I’ve argued, rather than not thinking about the natural law, judges should think about it better. In the same vein, should we say that rather than not thinking about the common good, judges should think about the common good better? Continuing my little digression, a distinction is necessary too. Anyone, whether a judge or a legislator, can understand the basics of the natural law. However, legislators are much better situated than judges are to work out their detailed, remote implications. For this reason I think the case for deferring to legislative judgments of what the natural law requires is strong when we are thinking of the details, weak when we are thinking of the basics. Perhaps an analogous distinction applies in the case of the common good. In this case, judges would have little or no authority to substitute their detailed judgments of what the common good requires for those of the legislature. But if the legislature blatantly pursued private interests instead of the common good, that might be a different kettle of fish. Here is another issue. Someone might suggest that in principle, judges should consider the common good, but the morally skeptical law culture, and the even more skeptical law school culture, in which judges are formed, makes it dangerous to allow judges the same degree of discretion that would be reasonable if these cultures were different. In England, it used to be said that the monarch had a power of prerogative – a power “to do good without a rule” – a power to do something for the common good even in the absence of a legislative rule explicitly authorizing what he wanted to do. John Locke remarked that the English parliament sometimes expanded and sometimes contracted royal prerogative, depending on its judgment of the moral character and wisdom of the king. Should we expand and contract the judicial “prerogative” in the same way? If so, then should the degree of discretion we are willing to grant judges in the name of the common good depend only on the moral character of judges, or also on the moral character of either the voting public or the legislators whom they choose? I distinguish the latter two groups because legislators might be either more or less virtuous than voters. Why is that? Because if voters choose the most virtuous legislators they can find, then those whom they choose may on the whole have even better moral character than they do; but if voters are either corrupt or deceived, then those whom they choose may on the whole have even worse moral character than they do. Knaves usually prefer to be ruled by scoundrels. Finally, how much should our answers to questions like these depend on long-term prudence, and how much should they depend on short-term prudence? For example, it is almost always prudent in the long term to practice separation of functions: Those who make general rules should be a different group of people than those who apply these rules to the adjudication of particular cases. But if one of these groups becomes profoundly untrustworthy, then someone might argue that in the short term it may be prudent to alter such arrangements. He might suggest that we may even resort to letting legislators judge, or letting judges legislate. Needless to say, such arrangements might be put into place for the wrong reasons. Considering them “thinkable” may make them even more likely to be put into place for the wrong reasons. Another drawback is that even if they are put into place for the right reasons, it might be very difficult to reverse them when they are no longer needed. In fact, they may tend to perpetuate the character faults that prompted their use in the first place, for those who are shut out of decisions tend to become even less capable of exercising good judgment. Don't say checks and balances will take care of all these problems. Checks and balances assume that legislators will be jealous of their authority and resist judicial usurpation, but legislators may even have motives to kick controversial decisions to judges. After all, they stand for re-election and judges don't. I don’t have answers to these questions or solutions to these difficulties. I’m just trying to frame them.

|

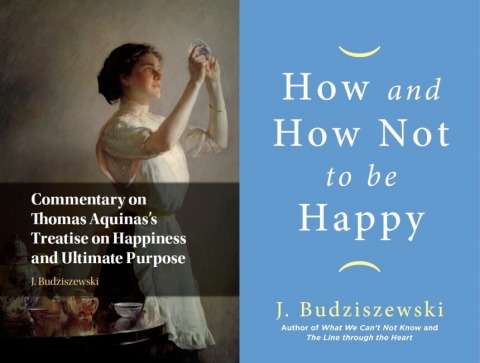

Two Little Announcements about HappinessThursday, 02-10-2022

People are always asking me when my Thomas Aquinas commentaries will be released in paperback editions because the hardcover editions are so expensive. The law commentary and the virtue commentary are already in paperback, and I’m pleased to announce that Cambridge University Press has just released the paperback edition of Commentary on Thomas Aquinas's Treatise on Happiness and Ultimate Purpose too. Better yet, until February 28, there is a 20% discount, knocking the paperback price from $39.99 to $31.99. To get the discount, go to www.cambridge.org/9781108745406 and enter the code CTATHUP22 at checkout. That’s good timing, because my new book from Regnery, How and How Not to Be Happy, will be released in hardcover on March 1. Although I always try to make all my books accessible to everyone, The Commentary on Thomas Aquinas’s Treatise on Happiness and Ultimate Purpose is primarily for students and scholars, but How and How Not to Be Happy is aimed squarely at general readers. More about the latter book in a few weeks! Cambridge says about the Commentary, “This monumental, line-by-line commentary makes Thomas Aquinas’s classic Treatise on Happiness and Ultimate Purpose accessible to all readers. Budziszewski illuminates arguments that even specialists find challenging …. This book’s luminous prose makes Aquinas’s treatise transparent, bringing to light profound underlying issues concerning knowledge, meaning, human psychology, and even the nature of reality.” The main sections are I. Man's Ultimate Purpose (Question 1); II. Happiness Itself; A. Where Does Complete Happiness Lie? Failed Candidates (Question 2); B. What Then Is Complete Happiness in Itself, and In What Does It Really Lie? (Question 3); C. Its Attainment; 1. What Complete Happiness Requires (Question 4); 2. How Complete Happiness Is Finally Attained (Question 5). “Budziszewski's Commentary on Thomas Aquinas's Treatise on Happiness and Ultimate Purpose provides an in-depth, detailed, accessible, and comprehensive commentary on the Summa theologiae's questions on happiness. This commentary is a gem. It can be read with profit by philosophers, theologians, and intellectual historians, as well as by their students. If you are interested in Aquinas, want insight about happiness, or both, this book is for you.” -- Christopher Kaczor, author of The Gospel of Happiness and Thomas Aquinas on the Cardinal Virtues.

|

A Little SecretMonday, 02-07-2022

Here is a little secret that you can get cancelled for telling: So called sex change doesn’t change sex. Among other things, the brain is already indelibly stamped male or female. Injecting hormones does not erase the stamp, and amputation of the genitals or breasts does not affect the brain at all. We might as well say that if I have my vocal cords severed, my limbs surgically altered for running on all fours, and my skin stimulated to grow a pelt, I will be a fox. No, I will be only a mutilated man. For details you can see the notes at the end of this post, but brain physiologists tell us that large parts of the brain cortex are thicker in women than in men. Ratios of gray to white matter vary, too. The hippocampus, which plays a role in memory and spatial navigation, takes up a greater proportion of the female brain than of the male brain. On the other hand, a certain region of the hippocampus is larger in the male. A variety of neurotransmitter systems work differently in men and women. The right and left hemispheres are more interconnected in female brains than in male ones, and the corpus callosum, which links them together, is larger. The amygdala, involved in emotion and emotional memory, is larger in men, but the deep limbic system, which is also involved in emotion, is larger in women. Sex-related differences between the hemispheres exist for other brain regions as well, including the prefrontal cortex, involved in personality, cognition, and other executive functions, and the hypothalamus, which links the nervous system with the endocrine system and has some connection with maternal behavior. External circumstances, such as chronic stress, act on male brains differently than on female. Brain diseases diverge in men and women, not only in frequency, but in age of onset, duration, and the way they manifest themselves. Even the neurological aspects of addiction differ between the two sexes. Is carving people up and pumping them full of chemicals going to change all that? By the way, although we should always be compassionate, compassion does not lie in encouraging souls who suffer delusions about their sex to sink even deeper into delusion, and to dope and mutilate their bodies. The evidence does not even support the claim that persons who have had so-called sex change surgery are happier after the damage is done. Thinking that happiness is getting what one wants, they often believe that they will be happier, but by and large all their former psychological problems persist. One of the best and largest studies, carried out in Sweden, found that “Persons with transsexualism, after sex reassignment, have considerably higher risks for mortality, suicidal behavior, and psychiatric morbidity than the general population.” A man who eventually had his sex change surgery reversed writes poignantly, “Nothing made sense. Why hadn’t the recommended hormones and surgery worked? Why was I still distressed about my gender identity? Why wasn’t I happy being Laura? Why did I have strong desires to be Walt again?” May I make a modest suggestion? Let’s stop calling it “kindness” to tell lies to unhappy people. It may make us feel good, but it shouldn’t. NotesDoreen Kimura, “Sex Differences in the Brain”Larry Cahill, “His Brain, Her Brain”Larry Cahill, “Why Sex Matters for Neuroscience”Related:On the Meaning of Sex

|

A Vaccine for BitternessMonday, 01-31-2022

There is another pandemic, far worse than the coronavirus, a plague of cultural insanity. At present I am not trying to argue the point, but speaking to the multitude who already know. The superspreaders of the plague don’t see themselves as crazy, and they have a lot of power to do harm. Needless to say, contagious madness has to be resisted and argued against. But there is so much sickening venom in public discourse! How can anyone swim against the flood of bitter poisons without swallowing some of it and becoming sick himself? It is easy to rant against ranters, to be bitter against the bitter, and to go mad in opposing insanity. But that doesn’t help a bit. Allow me to announce the vaccine for contagious madness: Humor. And I am not joking. Though it wasn’t a sidesplitter, I hope the last sentence gave you at least a very small smile, because the superspreaders of the plague are utterly humorless about themselves. St. Thomas More’s remark that “the devil … cannot endure to be mocked” is familiar, but the passage in which it appears is not so well known, and is well worth quoting too. This is from More’s Dialogue of Comfort against Tribulation, written while he was in prison for conscience -- a circumstance in which the reason of a less virtuous man would have tottered. Though the temptation to bile and bitterness must have been very great, More makes a strength of it: Some folk have been clearly rid of [certain] pestilent fancies with very full contempt of them, making a cross upon their hearts and bidding the devil avaunt. And sometimes they laugh him to scorn too …. And when the devil has seen that they have set so little by him, after certain essays, made in such times as he thought most fitting, he has given that temptation quite over. And this he does not only because the proud spirit cannot endure to be mocked, but also lest, with much tempting the man to the sin to which he could not in conclusion bring him, he should much increase his merit. The great saint is not speaking of the sort of thing that passes for humor among most of today’s comics and funny men. The wrong kind of mocker laughs goodness and innocence to scorn, and he cannot bear to be mocked any more than the devil can. But the right kind of mocker is a cheerful friend of archangels, who destroys wicked pretense by showing how silly it is, and does not mind being mocked by silly people. May we all become humbler scoffers, godlier mockers, and more fruitful fools.

|

For No Other Reason?Monday, 01-24-2022

An Op-Ed piece in the Los Angeles Times begins with the dismal words, “At the start of this new semester, we face a sobering reality. As law and political science professors, we’re in new territory: instructing our students about the foundations of constitutional law when neither they nor we have faith that the current Supreme Court will respect precedent and approach the law as the institution once had.” It speaks volumes about near-monoculture of contemporary academia that the authors can simply take for granted that all students and all professors of law and political science share both their dismay at the direction of the Court and the leftist ideology that produces that dismay. Leading their litany of lamentations is that “Students see a court about to overrule or gut Roe vs. Wade, a half-century-old precedent, for no reason other than that the conservatives have the votes to do so.” “For no other reason”? If the former remark spoke volumes, this one speaks libraries. Apparently the authors no longer even consider themselves bound to acknowledge that social, moral, and judicial conservatives have any arguments at all for what they do. Try the following reasons. One might argue against them. No doubt the authors would. But pretending that they don’t exist is nothing but hubris. ● No right to abortion is mentioned in the U.S. Constitution, nor does any such right follow logically from those that are. This right is supposedly based on a privacy right, which is treated as an autonomy right, which is treated as an I-get-to-do-what-I-want right, which also isn’t in the Constitution. ● Roe’s argument purporting to discover such a right in the Constitution was so badly reasoned that even many pro-abortion scholars decline to defend it. ● Moreover, the opinion in Roe was based on a demonstrably false judicial history. There was not a traditionally recognized right to abortion. ● Decreeing that we may not overturn any long-established precedent, no matter how specious and unjust, reduces jurisprudence to a farce. Among other things, it would have forbidden overturning the precedent that declared slaves to be chattel. By the way, Roe reversed the preexisting pattern of not recognizing any so-called abortion right, and overturned the laws of all fifty states. ● The unborn child is not a “potential” human life but a real one. From the moment of conception, he or she is both fully alive and fully human. We may concede that the baby is not fully developed; neither is a five-year-old. ● Nor is the child merely a part of the mother’s body. Though inside her body, this little being is a distinct individual with unique DNA. Mother and child may even be of different sex and have incompatible blood types. ● So-called “viability” is not a measure of human worth, but merely a shifting index of our medical abilities to date. In the broad sense, not even born infants can survive outside the womb without continuous care. ● Abortion cannot be a “reproductive right,” because it has nothing to do with enabling people to reproduce. It is not even merely an anti-reproductive right, because rather than just snuffing out fertility, it extinguishes a life. ● Nor can abortion be a “woman’s right.” The purpose of human rights is to protect human goods. The very suggestion that it could be good for mothers to set them against their own offspring is an insult to women and a setback to the cause of their dignity. ● The raison d'être of law is the common good. Authorizing the private use of lethal violence against the weakest and most vulnerable does not advance the common good, but despoils and overturns it. ● All rights presuppose the right to innocent life. If innocent human beings lack even the right to live, then there are no human rights at all. ● Finally, abortion is murder. No doubt the interpretation of the fine points and remote implications of the natural moral law should be left to legislatures. But permitting the slaughter of innocents offends the most basic principles of justice, apart from which the edicts of rulers have no claim to authority whatsoever. These reasons might have been sufficient, if only they had existed.

|

Free Exercise of What?Saturday, 01-22-2022

Judges and lawyers tend to think that some systems of absolute commitment and belief are religions and others aren’t. Anthropologists would laugh at this idea. In the broad sense, they all are. The important thing is what kind they are. Once we see this, we realize that religion in the sense of the Constitution – religion the Free Exercise of which is protected by the First Amendment -- can’t possibly refer to religions in that broad sense. Why not? Because in the original meaning of the term, exercising a religion means more than believing in certain things; it also means doing certain things and living in a certain way. To think that the Framers would have wanted to protect the “exercise” of, say, an assassination cult, is absurd. The courts are afraid to grasp this nettle. Bizarrely, they try to construe the meaning of the clause concerning the free exercise of religion without settling the meaning of the words in it – especially that prickly word “religion.” Their favorite sidestep is to say that law must be “neutral” about religion -- as though one could determine what it means to be neutral about it without knowing what it is. There is no such thing as neutrality. No way of dealing with religion is neutral toward religion; every way of dealing with it is some way of dealing with it. Besides, the Framers plainly didn’t intend neutrality between religion and irreligion anyway. They guaranteed the free exercise of religion as a protection for religion, and they wanted to protect religion because they thought it was good. The Supreme Court concedes this fact even in the act of denying it. In the 1963 case Abington v. Schempp, it oxymoronically remarks that one of the reasons for neutrality lies in the Free Exercise Clause, “which recognizes the value of religious training, teaching and observance.” Though it seems almost too obvious to point out, to assert the value of religion is not to endorse neutrality between religion and irreligion, but to say that religion is better. But the Framers must have intended the word “religion” to mean something, or the Free Exercise Clause is empty. So what did they mean by it? To put it another way, how can we pin down, without being arbitrary, the sense in which the clause uses the term “religion”? How can we determine which kinds of religion are the kinds to which the Clause refers? Although most of the Framers were Christians, I think they were using the term “religion” in a broader sense than Christianity – though not infinitely broad. They were referring to those truths about God that can be ascertained by reason, even if one does not have the additional data of revelation. And if we look at the way they actually wrote, then I think we can easily find out they thought these truths were. Consider just the Declaration of Independence. It speaks of “the laws of nature and nature’s God.” It says that the “Creator” has endowed us with certain liberties. And it appeals to “the Supreme Judge of the world,” expressing “firm reliance on the protection of divine Providence.” These were not empty pieties. I think it is reasonable to conclude that by religion, the Founders meant something like providential moralistic monotheism with a high view of the human person. To explain: By the word providential I mean they believed that God is paying attention. Ministers invited to address colonial legislatures taught that God would protect the country’s cause against the injustice of England, but only so long as the country itself behaved justly. Even the Deist, Thomas Jefferson, confessed that he “trembled” to consider how God’s justice would deal with the country in view of the injustice of slavery. Abraham Lincoln viewed the Declaration’s statements about equality as a promissory note, a public commitment implying a duty to eliminate that evil as quickly as possible. By the word moralistic I mean they believed that by having created nature, God is also the author of the natural moral law. It would seem to follow that freely exercising religion – by contrast with freely exercising sham religion and idolatry -- could not include acting in violation of this law. Writers of the time all conceded that the basic precepts of this law were well summarized by the Ten Commandments. By the word monotheistic I mean they believed that there is one God, and only one God, and that this God is not Me, or Us, or the All, but the Creator of myself, of us, and of the All. Were there more than one God, there might have been multiple, competing creations, or multiple, competing moral laws. Presumably, then, narcissists, polytheists, pantheists, and atheists might enjoy lots of liberties -- free speech and assembly and so on -- but would not enjoy whatever additional protection the Framers had in mind for religion. By saying they held a high view of the human person I mean they believed that having made us in His image, the Creator not only laid duties upon us, but gave us rights – and a good thing, because without the liberty to do our duty, how could we do it at all? These are not rights against God – they are rights against each other. You may not make me your tool. You may not deprive me of innocent life, or of the requirements for living humanely. Nor may you prevent me from serving God Himself. Whether or not we approve of this approach to religious liberty, I think it is probably what the Framers had in mind. It does not officially establish any particular religious sect in the sense of giving special legal status to it – but it is anything but religiously neutral. For it privileges all those sects that are providential, moralistic, and monotheistic with a high view of the human person – and it disprivileges, even though tolerating, the rest.

|