The Underground Thomist

Blog

Is Inconsistency Really Just a Hobgoblin of Little Minds?Monday, 06-12-2023

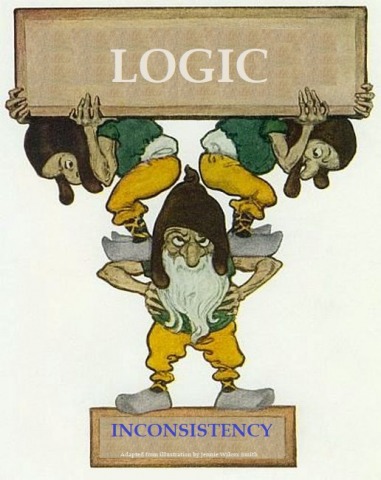

In a previous post I commented on the attack on Aristotle’s Law of Excluded Middle – that a meaningful statement is either true or false, with no in-between. Today I’d like to comment on the related attack on his Law of Non-Contradiction, that no meaningful statement can be both true and false, in the same sense, at the same time. At stake is whether reality can be inconsistent. Some claim that the possibility of inconsistent realities is proven by Schrödinger’s cat. I am referring to a famous thought experiment in physics, in which a cat is locked in a box with a tiny bit of radioactive matter, along with a vial of poison gas, connected via a relay with a Geiger counter. If a radioactive nucleus decays, the vial of gas is shattered and the cat dies. If it doesn’t decay, no gas is released and the cat lives. The claim of the contradiction-mongers is that until the box is opened and the condition of the cat is observed, the cat is both dead and not dead. No: Until the box is opened and the condition of the cat is observed, we simply don’t know whether it is dead or not dead. True, the possibility that the cat is dead coexists with the possibility that it is not dead, but this in no way suggests that the dead cat coexists with the live cat. It turns out that this was Schrödinger’s own view too! Although the predictions of quantum theory have proven highly accurate, the notion that they show that the principle of non-contradiction can be violated is nonsense. Unfortunately, the more outré interpretations of what is going on with the cat receive more attention from science popularizers than the sensible interpretations do. If we understand truth as correspondence – if the thought expressed by the proposition “Snow is white” is true if, and only if, snow is white in reality – then it is difficult to imagine what anyone who says “Snow is white, and also snow is not white” thinks he is asserting. In fact, the statement that propositions can be both true and false would itself be both true and false. What is one to make of that? Moreover, it has been known for centuries that from a contradiction, literally anything can be shown to follow. For example, if snow is white, and also snow is not white, then it follows that God exists. And that fairies like ice cream. And that God doesn’t exist. And that fairies don’t eat at all. And that it isn’t true that snow is white. All possible inferences can be made. This calamitous result is sometimes called “explosion.” Given the principle of explosion, it would seem that whenever there is an inconsistency in a system of propositions, the game is up. But can we give up the game so easily? Sometimes, when we are dealing with enormous systems of propositions, we know that there are probably some inconsistencies in there – and we will try to get rid of them when we discover them – but in the meantime, we don’t know what they are. This being the case, it might be helpful to develop a way to insulate the rest of the system from so-far-undiscovered inconsistencies – to cautiously keep using the system while we are trying to find them and root them out. This is something like what computer programmers do when they try to develop programs that won’t crash every time, even though the programs inevitably still contain some bugs. Now some people who talk about such “paraconsistent” logics speak as though they thought a proposition really could be both true and false in the same sense at the same time – which requires believing that a thing can both be and not be in the same sense at the same time. This is called dialetheism, and to call it “badly confused” seems generous. But sometimes people who talk about paraconsistent logics speak more as though they are trying to develop coping strategies of the sort that I mentioned in computer programming. Their thought is merely that we may have to tolerate contradictions provisionally, while we are trying to find out what they are. This may not be insane, and may even be important -- although perhaps it is misleading to call the development of coping strategies “logic.” It might be more accurate to say that the goal is to protect logic from the illogic we haven’t yet caught.

Copyright © 2023 J. Budziszewski

|

Fuzzy Logic Is Fuzzy ThinkingSunday, 05-28-2023

Aristotle famously said that a meaningful statement is either true or false; there is no in-between. This is called the Law of Excluded Middle. However, a great many people say there can be in-betweens, and even try to axiomatize the idea. Sometimes this is called “fuzzy logic.” I think it’s fuzzy thinking. Superficially, the idea is plausible. After all, don’t we say that there are half-truths? We do say that, but only figuratively. The expression “half true” never means literally that a meaningful proposition can be something other than true or false, or that a state of affairs can be intermediate between reality and unreality. It may mean quite a number of other things, for example: 1. Someone might call the statement “Shale is a sedimentary rock” half true because he has only 50% confidence that it is true. Yet irrespective of how sure he is, the statement that shale is sedimentary is either true or false -- and irrespective of what kind of rock shale is, the statement that he has only 50% confidence about it being sedimentary is also either true or false. 2. Someone might call the statement “The cloth is white” half true because its actual shade is halfway between white and black. Yet what he means is that the cloth is gray, and the statement “The cloth is gray” is 100% true. 3. Someone might call the statement “Calico cats are even tempered” half true because the description applies to only half of all calico cats. Yet the more precise statement “Half of all calico cats are even tempered” would in this case be simply true. 4. Someone might call the statement “We have here a heap of sand” half true because the term “heap” is vague; there is no fixed number of grains above which an accumulation becomes unambiguously a heap. But by choosing to call a certain accumulation of sand a heap, he is using a noun as an oblique way to express a matter of degree – he is choosing to emphasize how much sand there is rather than how little. So saying “We have here a heap of sand” is like saying “Gee, what a lot,” or “There sure seems a lot of it to me.” And either there does seem a lot of it to me -- or there doesn’t. 5. Someone might claim that the statement "The unborn child is a person" is half true on grounds that the unborn child is only a potential person (in fact, this claim is rather common!). But although the unborn child has some unrealized potentialities – as a toddler does, or as the reader of this paragraph does – still, if the child weren’t already wholly a person, the child wouldn’t have these potentialities. A bone cell doesn't have such potentialities; a gamete doesn’t have them either. But from the moment the zygote comes into being, the zygote does. 6. Someone might claim that the statement “This theory is true” is half true because the theory consists of a number of different propositions, and not all of them are accurate. But taken one at a time, each of these propositions is either true or not. Rather than saying that the theory is half true, we should say something like “Half of its claims are true.” 7. Or take Objector 1’s statement, “Every intellect is false which understands a thing otherwise than as it is.” Someone might call it half true because it is true in one sense but false in another. But to say so is to admit that in each sense it is either true or false – not something in between. None of these possibilities shows that there are values of being between true and false. Moreover, each of these possibilities needs to be handled in its own way. Unfortunately, a system of inference which calls them all “half truths” treats them all the same. For as we see, ● Possibility (1) doesn’t show that there are degrees of truth, but only that I may be more of less sure about what really is true. Instead of speaking of degrees of truth, we should speak of degrees of confidence. ● Possibility (2) doesn’t show that there are degrees of truth, but only that some things are more or less. Instead of speaking of degrees of truth, we should speak of degrees of qualities. ● Possibility (3) doesn’t show that there are degrees of truth, but only that some facts concern fractions or proportions. Instead of speaking of degrees of truth, we should make use of our arithmetic. ● Possibility (4) doesn’t show that there are degrees of truth, but only that some ways of describing how much of something there is are indirect. Instead of speaking of degrees of truth, we should pay closer attention to oblique modes of description. ● Possibility (5) doesn’t show that there are degrees of truth, but that our grasp of personhood is defective. Instead of speaking of degrees of truth, we should clean up our careless metaphysics. ● Possibility (6) is something like possibility (3). It doesn’t show that there are degrees of truth, but only that there are fractions. Instead of speaking of degrees of truth, we should distinguish among the propositions in the theory. ● Possibility (7) doesn’t show that there are degrees of truth, but only that some statements are ambiguous. Instead of speaking of degrees of truth, we should say what we really mean. Other examples besides these seven can be suggested. For example, someone might call a proposition half true because it resembles the truth, because it figuratively expresses the truth, or because it could have been true, but isn’t. Someone might call a classification half true because an object is difficult to classify, because fits into more than one classification, or because no suitable classification for it has been devised. Someone might call the statement that Pegasus is a winged horse half true because Pegasus exists only in the story and not in reality. Someone might call the statement that a child is an adult half true because the child has traversed half of the distance toward being an adult. Someone might call the description of a patient as “still alive” half true because the patient is dying. And, of course, someone may call affirmations about God half true for all sorts of fuddled reasons. But in no cases whatsoever do we actually encounter states of being which are neither true nor false but something in between. So the figure of speech “half true” is merely an amusing, ambiguous shorthand for things that more clearly be said differently, and does not describe what is actually the case. The fact that we can devise formal systems of inference for so called half truths does not show that there are, in fact, states of affairs that are half so -- any more than the fact that we can formulate syllogisms about things that taste like the number seven shows there are, in fact, things that taste like the number seven.

Copyright © 2023 J. Budziszewski

|

Antipasto IIMonday, 05-22-2023

More quick thoughts to stimulate the intellectual digestion. (See Antipasto I.) +++ + +++ A poster in my campus’s business school building is emblazoned with the slogan, "Leading at the Edge of Disruption." Yes, I understand about innovation. But how did breaking things become the preferred metaphor for the sorts of things accountants and managers do? Hierarchies can be egalitarian, if they give equal treatment to those who are equal in merit, and if they treat only unequals unequally. Egalitarianism can be authoritarian and punitive, if it treats those who are unequal in merit as equal. Terrorism is contagious, and some terrorist theories actually count on the fact. Their idea is that in order to fight fire with fire, the government will become so oppressive that at last the population will turn against it. And then the terrorists have won. Social scientists often construct vast models with causal arrows spearing off in all sorts of directions – that influences this and that, and this influences that and this. I wonder: Haven’t those who construct these models noticed that social structures change constantly? Even if all the causal relationships really could be sorted out and measured, by the time the researchers finished doing so the relationships would all be different. This is why political philosophy does best when it focuses on what has been called the permanent things. The boast of some of these models is that can “predict” the outcome of, say, every recent election, going back years. They can, but only retroactively. Whenever their predictions turn out wrong, the researchers go back and tinker with the parameters until they would have turned out right. That doesn’t mean the models will predict the next election right. What an exercise in futility. Although deceiving ourselves is something like deceiving others, there is one great difference. If I lie to you cleverly enough, you really don’t know that I am lying. If I lie to myself, then no matter how clever I am, at some level I do know that I am lying. So when I lie to you, I have to keep you from noticing -- but when I lie to myself, I have to keep myself from thinking about it. A student told me there were no objective moral truths. I mentioned a precept of the Decalogue, and asked “What about that?” He replied, “That’s not morality, that’s justice.” But if we take justice in the classical sense – giving to each what is due to him – almost all morality is about justice. To my wife, I owe fidelity; to my parents, honor; to the child whom I sire, an intact family in which to enjoy the care of me and his mother. Though I can never keep up with it, I am endlessly fascinated with slang and its origins. People who know this often recommend to me the Urban Dictionary. Unfortunately, its definitions are submitted by users, and it is transparently obvious that many users find it amusing to invent filthy definitions for every word and phrase they can think of. The words and phrases may not have had filthy meanings before. But thanks to this so-called web resource, they do now. People tend to think of souls as something only humans have. No, even a plant has a “soul,” just in the sense that its embodied life has a pattern. The difference is that the plant’s “soul” dies with the plant -- but for us, not so. The pattern of an embodied human life – which is a rational life -- persists even in the absence of the matter of which it is the pattern. But the human body is a part of human being too, and so the Christian hope is not an eternal bodiless existence, but bodily resurrection. One soon wearies of all the nonsense spouted about “spontaneous order.” If taken to mean that the order we see does not entirely preexist, then yes, some forms of order are spontaneous – markets, for example. But if taken to mean that no elements of order need to preexist, then no, because there has to be a lot of prior order before other order can develop. Think how many shared understandings the development of a market requires. Failure to distinguish the reasonable from the impossible sense of spontaneity leads to big confusions, like thinking that the theory of natural selection eliminates the need for a creator of the physical principles that make natural selection possible, or thinking that because the mind learns from experience it has no inherited structure. Concerning that inherited structure, the mind is not pre-loaded with moral knowledge of good and evil – a toddler doesn’t know the Golden Rule. So don’t talk about innate moral knowledge. On the other hand, the mind does have the properties that allow it to recognize good and evil when it attains the age of reason. Even a blank slate must be made of a material that can take on the forms of the letters; try to chalk words on the ocean. Scholars sometimes say that different views of Constitutional interpretation are like different views of biblical interpretation. Some people say sola scriptura, others say that the written text makes sense only in the light of the unwritten text. There is something to this analogy, but it breaks down quickly. I hope no one is insane enough to attribute allegorical meaning to the Privileges and Immunities Clause. Sometimes people vote for persons who promote unconscionable views because they really believe in these views. However, sometimes they vote for them for irrelevant reasons – for example, they may trade their pro-life views for lower taxes. But in order to quiet the protests of their conscience, they may then try to talk themselves into believing in the evil views too. Differences among interests and points of view within a shared moral framework is good for a polity, but where did we get the idea that radical divergence of basic moral outlooks is also good for it? Social scientists have known for some time that conservatives understand what liberals believe much better than liberals understand what conservatives believe. I notice, however, that a good many progressive voters don't even understand what their own opinion leaders believe. When you quote these leaders, quite a few people of the progressive persuasion will say to you, “You’re making that up. No one would think that.” Or that no one would teach it to public school children. When the republic is finally destroyed, it will be taken down in the name of saving it from its destroyers. As a Christian, I believe in the Messiah. That doesn’t mean I have to like political messianism, which we find both on the right and on the left. The difference is that left-wing political messianism is usually utopian, trusting the hero to take us to a political promised land -- but right-wing political messianism is usually reactive, trusting the hero to save us from the crazies who believe in utopia. The advantage here lies with the left, because unfortunately, most people are more impressed by lunatic visionaries than by persons with no vision at all. Except for obscenity, profanity, and fighting words, I don’t believe in policing the words we use in public. But I do understand the temptation. If I could make a wish, I would wish that everyone who used junk words like “wellness,” “impactful,” “proactive,” and “mindfulness” felt a bit ridiculous. A warning to intellectuals such as myself. Supposing the existence of square circles, you can do a lot of things: You can make syllogisms about them, you can develop theories about them, you can even prove theorems about them. But that doesn't mean that they exist.

|

Do All Dogs Go to Heaven? The Debate ContinuesMonday, 05-15-2023

Sometimes it’s fun to speculate about things about which we know nothing. For animal lovers, one of these speculations may be dead serious. I’ve written before about Thomas Aquinas’s argument that the “soul” of a beast – the pattern of its embodied life -- perishes upon the death of its body, because all of the powers of its soul are utterly dependent on its body. By contrast, the rational soul of a human being is capable of conceiving universals, which transcend the body. Although bodily senses perceive only singulars -- this water, this food, this enemy – the rational soul conceives water as such, food as such, or an enemy as such. Since there is something in the rational soul that is not dependent on the body, the rational soul can survive the body’s death. Perhaps this reasoning is a bit hasty. Even on St. Thomas's premises, if the rational power could be added to the beast's soul, it could survive death. The obvious objection to such a possibility would be that since such an addition would involve a change in the very essence of the beast, the original beast would indeed have perished – what now exists would be a new beast. But there may be a way around the objection. The soul of the beast could survive death if a certain thing happened to be true. This is purely a what-if argument. First consider the rational soul again. According to St. Thomas, not even the rational soul has in itself the potentiality to see God. Rather God adds to the souls of the redeemed the power to see Him in the next life. It might seem that here, too, we are supposing a change in essence, so that it would not be us seeing Him, but entirely new beings seeing Him. But St. Thomas says this is not the case. Why not? Because although our nature does not possess the potentiality to raise itself to the vision of God by its own powers, it does have a receptive potentiality to receive from God the vision of Himself. For a nature to receive what it has a potentiality to receive does not change it in essence but rather completes it. Thus we are not destroyed by receiving the vision, but rather uplifted. Is it possible that the beasts too have a receptive potentiality, though of a lesser kind? Could it be that unknown to us, God has endowed them, not with the potentiality to raise themselves to rationality on their own, but to receive from God Himself the power of rationality? In this case, just as the acquisition of the power to behold God would uplift rather than destroying a rational being like you and me, so the acquisition of the power of rationality – presumably, at the point of death -- would in a lesser degree uplift rather than destroying a beast. Fido would still be Fido – but rational, as we are already. Turn the question around. Can we be certain that no beast nature does contain a receptive potentiality of the sort I have in mind? If we take the story of Balaam’s ass* literally, such certainty may be a bit reckless. But suppose God did bestow rationality upon a beast possessing the potentiality to receive it. In this case, the beast, now elevated to rationality, could survive the death of its body after all. Related:Do All Dogs Go to Heaven?*The relevant part of Balaam’s story is given in Numbers 22:22-44.

|

Things I Had to LearnMonday, 05-08-2023

There are so many things I took much longer to learn than I should have. Here is an incomplete list. +++ + +++ There is nothing wrong with old ideas, so long as they are true. And there is nothing admirable about new ones, if they aren’t. There are some truths which do not have to be proven, but are needed for working out all the other truths. Even the most obvious things can be doubted. The test of a truth is not whether I doubt it, or whether I am able to doubt it, but whether the reasons for thinking it is true are better than the reasons not to. There are a great many truths that we can’t help knowing at some level. Even so, we may not be aware of knowing them, we can deny knowing them, and we can pretend to ourselves that we don’t know them, The fact that I suppress what I know and pretend not to know it, even though I do know it, does not keep my buried knowledge from influencing my actions – but, since I suppress it, it distorts my thinking and influences my actions in a perverse way. We like to ask “If there is a God, why is there any evil?” Here is a better question: If there isn’t a God, why is there any good? Wisdom is a virtue, not a talent, and so it is not the same as mere intelligence. Intelligence is a talent, not a virtue. Even so it is less about sheer ability than about the organization of personality. There is more than one kind of intelligence, and I am a fool if I dismiss the kinds I don’t have as unintelligent. The only remedy to the abuse of truth is more truth. Suppressing truths because they seem likely to be abused is futile, because they are all likely to be abused. For the more truth a falsehood contains, the more persuasive it becomes, and so the more useful it is in making excuses for evil. If an error or deception did not contain at least a grain of truth, no one would fall for it. The only remedy to injustice is to do justice. So called reverse discrimination is not the reverse of discrimination. It is only injustice with a new set of perpetrators. Reparations are not due from the innocent. Some natural selection buffs claim that the human mind is just a meaningless and purposeless result of a process that did not have us in mind. Hold on a moment. If it were, then there would be no reason for confidence in any conclusion of reasoning whatsoever – including the conclusion that our minds are a meaningless and purposeless result of a process that did not have us in mind. No one can invent new values or a new morality. What appear to be new ones are merely the results of cherry-picking elements of the “old” morality, exaggerating them, and ignoring all of its other elements. This was Lewis’s great insight. The greatest blessings we receive in life are undeserved. For example, I didn’t do anything to deserve good parents. On the other hand, it is not unjust for a person to have such a blessing, and it is not an act of justice to try to erase it. What justice requires is gratitude for blessings received. What charity requires is trying to act in a way that blessings of the same kind may be more widely enjoyed. The two great natural goods of marriage -- the turning of the great wheel of the generations, and the union of a man and woman who cooperate in turning it -- cannot be separated without damage to each of them. To suppress either one for the sake of happiness is to poison the very roots of joy. The reason we have sexual harassment is that we do not believe in chastity. In the end, the only way to discourage unwanted advances is to condemn immoral ones. To discredit sexual harassment, one must discredit sexual sin. Sins are not "mistakes." Mistakes are things we didn't mean to do. To give the appearance of doing wrong, when it could have been avoided, is to do wrong. This used to be called the sin of scandal, but we have misappropriated that useful word and put it to different purposes. Refusing to repent is equivalent to refusing to be forgiven. We say we must “forgive ourselves” -- but no one can really forgive himself, because he is not the one who is principally concerned by his wrongdoing. Instead one should confess wrong and seek forgiveness from that person – and from God. One who has been unable to trust his father has a much more difficult time learning to trust the One from whom all fathers take their name. A feeling cannot be promised. When we promise love, therefore, we are not promising to have a feeling. What we are promising is an enduring commitment of the will to the true good of the beloved – even when feelings change. Love without truth is an illusion. To spare someone the truth is not worth the name of love. If he is hurting himself, telling him so is not judgment but compassion; not telling him is not compassion but indifference. This list is about things I was slow to learn, and that last one wasn’t really hard for me. But to tell such things in just the right way and in just the right season – and to listen to what I need to hear in turn -- that was.

|

Is Pride Really Graver Than Murder?Monday, 05-01-2023

Query:In considering the relative gravity of sins, Aquinas considers pride in itself as graver than murder, since pride, in its proper meaning, is by its very nature a turning away from God. Murder in its nature constitutes an unjust taking of life, and turning away from God is its consequence, not its essence. I get that. However, we don’t usually say that blasphemy or unbelief is worse than murder, even though that too is a turning away from God. I think the reason we say it about murder but not about blasphemy or unbelief is that a concrete act of murder involves not only the unjust taking of like but also a turning away from God. If I’m right, this would make murder graver than blasphemy. Do you think this makes sense?

Reply:I take it that you’re reflecting on Summa Theologiae, II-II, Q. 162, Art. 6. You make a good point, but there is more to be said. Perhaps St. Thomas would offer considerations something like the following. First, remember that he is not speaking of particular acts of pride and murder, or of murder as a result of pride, but of pride in itself and murder in itself. When we are making comparisons, he says, “that which belongs to a thing by its nature is always of greater weight than that which belongs to it through something else.” So we need to consider the matter from more than one perspective. Pride -- understood not as, say, satisfaction in having done a job well, but as turning away from God and treating ourselves as gods -- is the father of all sin, because it radically disorders us. If our minds refuse God’s governance, then they are no longer capable of governing the passions, the appetites, or for that matter themselves. Moreover, tearing our minds from His keeps us from understanding the proper relationship among proximate goods, because we no longer see them in their true relation to our ultimate good, which is nothing but Himself. If turning away from God is worse than murder, why doesn’t human law treat it as worse than murder? Mainly because human law is in charge of the temporal common good, not the spiritual common good of union with God. A secondary reason is that unbelief is an invisible movement of the heart, which human beings cannot see; human law can address itself only to outward acts, which it can see. Still another is that faith cannot be coerced; if unbelief were made illegal, the consequence would not be a nation of unbelievers, but a nation of hypocrites. The state is not is neither commissioned to look into hearts, nor capable of doing so. On the other hand, human law does consider treason and betrayal the worst of the sins it does have authority over – and there is an analogy here with divine law, because contempt for God is the worst of all possible treason and betrayal. By it, we destroy not just our bodies, but our souls, which are infinitely more important. Moreover, by expressing our contempt for Him outwardly, through deliberate blasphemy, we endanger our neighbors’ souls too. Murder only destroys their bodies. But if we think of the intrinsic gravity of sins rather than whether it is fitting to punish them by human law, I think St. Thomas would say that things look different. As he says, “aversion from God and His commandments, which is a consequence as it were in other sins, belongs to pride by its very nature.” Let’s think about this. When my children were small, whenever they disobeyed the parental precepts -- for example by snatching each other’s toys instead of sharing them -- they certainly put themselves at odds with us. One could say that in that sense they were also withdrawing themselves from the order of honor to parents, and so committing not one wrong but two. True. Even so, they didn’t snatch the toys because they had contempt for us; they snatched them merely because they wanted them. If they had acted directly from contempt for us, the wrong would have been much, much worse. I suspect that when the children did these things, they were not thinking of us at all -- or that if they were, they were thinking only of how to keep from getting caught. So even though disobeying them had the effect of withdrawing them from the order of honor to parents, it was not the same as the sin the very root of which was to dishonor us. Could it be the same with the case you mention? Murder has the effect of withdrawing us from right relationship with God and destroying charity, but it is not the same as the sin the very root of which is contempt for God and rejection of charity, and that is far graver. To have contempt for my neighbor, who is made in God’s image, is one thing, but to have contempt for the God in whose image my neighbor is made -- the very Being from Whom my neighbor draws his life and because of Whom that life has such enormous value -- is quite another. God is the reason why we and our neighbors are sacred; it is He alone who makes us persons, He alone who lifts us above being whats to the dignity of being whos. For all these reasons, we might even say that a murder is just a murder, but that the sin of pride virtually contains all murders.

|

Are Christians “Idealists?”Monday, 04-24-2023

Query:Are Christians idealists, in the sense in which a Marxist would use the term? You know I am at university in a Marxist country.

Reply:I think you may be asking any of four different things. Possibility one: Is a human being at bottom just a body (a material substance), or is he at bottom just a soul (an intellectual substance)? We believe that human beings are not bodies alone, or souls alone, but souls united with bodies. Many analytical philosophers call this view “dualism,” although I dislike the term because it can have more than one meaning. The more traditional name for the doctrine of body-soul unity is “hylomorphism.” Possibility two: Do nonmaterial forms really exist, or is matter all that exists? Certainly forms exist. Matter exists in time, but time is not matter. We have thoughts, but thought is not matter. A sentence has a meaning, but even though the meaning may be represented by ink marks on paper, the meaning is not the same thing as the ink marks on paper; in fact, the meaning is the same even if the matter changes – for example, if the sentence is represented by configurations of pixels on a computer screen. Possibility three: Granted that these forms exist, do they exist in themselves, as Plato thought? The traditional Christian view is that they don’t, so if that is what is meant by idealism, we are not idealists. Rather forms are found in three other places -- in things, in minds, and in the mind of God – though they are not found in these three places in the same sense, but in analogical senses. The form of the body “informs” the body; my grasp of this form is in my mind; and all forms of created things preexist in the mind of the Creator. This view is usually called moderate realism – realist, because it affirms the reality of forms, and moderate, because it does not suppose that they have independent existence. Possibility four: A Marxist would probably be thinking not just of Platonic idealism but of Hegelian idealism. I am no Hegel scholar, but subject to correction, I understand him to have thought that the world cannot be distinguished from how the world is understood, and that God or “Spirit” becomes conscious of itself in human minds. Orthodox Christianity rejects these views. God, who brought our minds and the world into existence, is distinct from our minds and the world. Simultaneously whole in every moment, He has no need to evolve. Knowing all things, He has no need of us to be conscious of Himself. Our minds are true when they correspond to how things are; things are as they are because they correspond to the mind of the Creator.

|