The Underground Thomist

Blog

NarcissusMonday, 12-04-2023

Recently I came across this unintentionally revealing statement by actress Drew Barrymore. “Being with a woman,” she said, “is like exploring your own body, but through someone else". Exactly.

|

Where Is Justice in Natural Law?Monday, 11-27-2023

Query:I am wondering how justice fits with traditional definitions of natural law. Aquinas mentions five fundamental natural law precepts, namely life, the procreative union of male and female, the education of the young, living in society, and the worship of God. Most natural law thinkers would also state that justice is a key principle of the natural law. However, it does not seem to me to be clearly stated within Aquinas’s fundamental precepts or to fit neatly with them. Reply:Very good question, but I think you have this difficulty with St. Thomas only because of a misreading – a common one. In the place in the Summa theologiae I think you have in mind, he says that the order of the precepts of natural law corresponds to the order of the natural inclinations, and he speaks of three inclinations – the inclination we share with all substances, the inclination we share with all animals, and the inclination which pertains more particularly to our rationality. You would think, then, that there should be only three fundamental precepts. The reason there are more than three is that his term “inclination” refers not to particular inclinations, as we would use the word “inclination,” but to broad categories of inclinations. These categories are pretty broad. In speaking of what we share with animals, for example, he gives two examples -- sexual intercourse and the education of offspring, as you note – but then he says “and so forth.” Rightly so, because we share a great many other things with other animals too, such as learning from sense impressions. Then, in speaking of our rationality, he mentions the inclination to seek the truth, especially the truth about God, as well as the inclination to live in society. Although this time he doesn’t say “and so forth,” once again these are just examples; they don’t exhaust the set of inclinations we have because of rationality. For instance, only a rational creature seeks beauty and tries to be witty. To back up for a moment, it’s pretty obvious how the inclination to know the truth is connected with rationality. But how is the inclination live in society connected with it? After all, don’t cows live in herds, and don’t birds live in flocks? And they certainly aren’t rational. Upon reflection, though, one realizes that what St. Thomas means here by society isn’t just how cows and birds hang around together, but partnership in a life shaped by truth and rational principle, something the beasts can’t enjoy. And now things really get interesting, because among the rational principles essential to such a partnership is justice, which is equal treatment of those who are equal in the relevant respects. So yes, we do have a natural inclination to seek justice -- and doing so is a fundamental precept of natural law. My correspondent had continued:I suppose there are two possibilities: one, that Aquinas’s definition needs to be supplemented by an additional precept, which leaves open the possibility that there are additional primary precepts of the natural law. I can imagine that this is an unattractive prospect for someone in the Thomist tradition! Reply:As you now know, this Thomist thinks there are lots of other primary precepts -- and that the prospect is not at all unattractive! To avoid getting St. Thomas wrong, it’s important to keep in mind his fondness for the figure of speech called metonymy: He often uses the most conspicuous instances of things as placeholders for entire sets of things, and this is what he is doing when he speaks of our inclinations. My correspondent had again continued:Another possibility is that justice is inherently related to the precept about human sociability. Because we have an inherent need to live in society, and we ought to do to others what we would have done to us, it follows that we ought to give every person his due. From this we could presumably deduce principles about impartiality, procedural fairness, etc. Reply:Right! And you know I agree, because your remark anticipates what I wrote a few lines above. Related:Commentary on Thomas Aquinas's Treatise on Law

|

On Doing What Comes NaturallyMonday, 11-20-2023

Query:The sources I’ve read say that according to Thomas Aquinas, human nature is characterised by certain natural dispositions or inclinations which need to be realized. Would you say that this accurately characterizes his view? The reason I ask is that it follows that whatever impedes the fulfilment of natural capacities is inherently evil. But this seems to prove too much. For instance, on this account the celibacy of a nun or a priest would be inherently evil, because it impedes the fulfilment of the natural tendency to procreate. If the view I’ve described is correct, then it might illuminate a key difference between Protestant and Roman Catholic approaches to sexual ethics. For instance, it seems to me that it is good to have children, and we have a natural tendency to do so, but it does not follow that every sexual act must be procreative or potentially procreative.

Reply:As to your first question: Thomas Aquinas does hold that for any given nature -- such as a human being -- the good is that to which it is naturally inclined, that which its very nature disposes it to seek. So far, so good. However, the language of “impeding fulfillment” is dangerously imprecise. Thomas Aquinas doesn’t think we must all be having sexual intercourse all the time just because there is a procreative inclination, any more than he thinks we must all be eating all the time just because there is a nutritive inclination. Let’s work through this. A power isn’t thwarted because I don’t use it, but because I don’t use it when I should use it, or because I use it at a time, or in a way, which frustrates its end or ends. Thus, going on a diet does not undermine the purpose of the nutritive inclination – but it would be would be wrong to overeat, induce vomiting, and then eat some more. Similarly, sexual abstinence does not undermine the purpose of the procreative inclination – but it would be dreadfully wrong to have sexual intercourse, but in a way which deliberately renders the act sterile. That would be something like eating and vomiting. Now as to your conclusion about Protestantism and Catholicism: I think you are blurring the distinction between not trying to have a baby, and trying not to have a baby. Catholic ethics does not teach that my wife and must be trying to conceive every time we enjoy marital intercourse; we may be simply expressing the love of our procreative union. Nor does it teach that we may never abstain; but when we do have sexual intercourse, we must be open to the possibility which it carries. We must never intentionally close the door to new life. Incidentally, you call this the Catholic approach to sexual ethics, but until the Anglicans broke ranks in the early 1930s, it was the Protestant approach too. Martin Luther agreed with it; so did John Calvin.

|

Tabula Rasa?Monday, 11-13-2023

Query:In the First Part of the Summa theologiae, Thomas Aquinas cites Aristotle to the effect that the intellect is like “a tablet on which nothing is written." That’s in the sed contra, his restatement of the traditional view. But then in his own response, he agrees: Man's potential knowledge is transformed into actual knowledge "through the action of sensible objects on his senses," so that the soul "has no innate species" (no innate knowledge of forms). WHAT? My whole academic life, I have been hearing that Locke rejected the innate ideas in which his predecessors supposedly believed, calling our minds a tabula rasa or blank slate. I must be missing something, because surely those critics had read this passage in Aquinas. Would you be so kind as to enlighten me as to why Locke is so different from Aquinas here?

Reply:Yes, I had the same reaction when I was first studying Aristotle and Thomas Aquinas! However, the notion of innate knowledge does not come from those two luminaries – I don’t know why people say this. And really, the notion is crazy. If there were such a thing as innate knowledge, then even the baby freshly popped from the womb would have it. Fancy a newborn thinking to himself, “I must never do anyone undue harm -- whatever doing is, whatever harm is, and whatever it is to be undue”! St. Thomas certainly believes in natural knowledge. He says so in the very section you quote. Of course he doesn’t think all our knowledge is natural, or else we would never forget anything, and even a blind person would know what color is. Now here’s the kicker. According to him, not even natural knowledge is innate. Even natural knowledge depends, in a way, on sense experience. Someone who had never had sense experience wouldn’t know anything. Let’s think about this. There are certain things that a person who has reached the age of reason naturally knows, but he isn’t born with this knowledge. For example, an infant doesn’t innately know that two things equal to a third thing are equal to each other. But when the proposition is taught to a twelve-year-old who understands the meanings of such terms as “equal,” he can’t help but see that it is true. The knowledge is per se nota, “known in itself.” Does he know it just because someone has taught it to him? No. Your mother and father taught you the Golden Rule, but you didn’t believe it just because they said it was true; you believed them because when they said it, you could see for yourself that it was true. What they did by their teaching was call your attention to this truth, and what they said made sense to you. Even per se nota knowledge depends on sensory experience, because if you had never perceived any things which were equal, you wouldn’t understand what equality is, and so you wouldn’t grasp that two things equal to a third thing are equal to each other. Yet in another sense such knowledge transcends sensory experience, because even though you haven’t seen all equal things, you know that the proposition “two things equal to a third thing are equal to each other” must be true – even of the equal things you haven’t seen! According to St. Thomas, the reason your mind can know such a thing is that the universal forms of things are implicit in sense experience, and the rational mind extracts them. A bird, which is not rational, knows only particulars: This worm, this branch, this nest. In fact, since it doesn’t possess the concepts of worm as such, branch as such, or nest as such, even that way of putting it falsifies the bird’s knowledge. All it really knows is this, this, this! By contrast, when you see a worm, you recognize it as an individual instance of worm. This is stupendous. Our power to grasp universal forms is what makes it possible for us to formulate predications: To say, for example, that man is a rational animal, or that undue harm must not be done. When a proposition is per se nota, the mind recognizes that the predication expressing it has to be true, just from the meanings of the terms it employs. The subject, man, contains the meaning of the predicate, rational animal, so of course “man is a rational animal” is true. The subject, undue harm, contains the meaning of the predicate, something that must not be done, so of course “undue harm must not be done” is true. By contrast, the proposition “the table is made of brass” is not per se nota, because the subject, table, does not contain the meaning of the predicate, made of brass. The table might be made of wood, plastic, dark matter, pixie dust, or something else. Now Locke doesn’t differ from Aristotle and Thomas Aquinas merely because he believes that the mind learns from experience. Locke differs from them because he and the other empiricists radicalize the idea, trying to make sense of it without recourse to real forms or essences. Aristotle and St. Thomas would have considered that impossible. And I think it is. You might think of it this way. The mind of a bird is a blank slate, and the mind of a human being is also a blank slate. But what can be written on the bird and the human being slates differs radically, and so does the way it is written there. The mind of a bird takes in only the particulars of a thing; the mind of a rational being takes in its form or essence. And just for that reason, the slate is not blank in the peculiar sense that some people give to the expression tabula rasa, for not just anything can be written on it – and some things can’t help but be written on it. There are some things that a rational being of the age of reason can’t not know, and cannot disbelieve even if he tries. Related:Commentary on Thomas Aquinas's Treatise on LawWhat We Can't Not Know: A Guide

|

If Conscience Is Real, How Can We Believe Foul Things?Monday, 11-06-2023

Query:In my country, lower caste Hindus feel inferior in relation to Brahmins, so that if a Brahmin were to rape the daughter of a lower caste Hindu, this would be considered a privilege. Doesn’t this cast doubt on the idea that conscience is available to all humans? It seems that humans can believe anything. Whatever is put into them by external authority, they seem to consider true. What is going on? Is their will truly not free?

Reply:One would think that since humans often both commit and comply with wrongdoing, conscience must be very weak. On the contrary, our deepest moral knowledge is incredibly strong, but we can go to great lengths in the attempt to escape it. To begin with the perpetration of wrong: The most interesting thing is not that we can tell ourselves that wrongdoing is right, but that we have to tell ourselves: Our consciences will not simply overlook what we have done. Moreover, the only way we can make wrong look right to ourselves is to take genuine moral truths and misapply them. I like to say that rationalization is the homage paid by sin to guilty knowledge. For example, it is impossible not to be ignorant of the wrong of theft, but I might rationalize the deed by telling myself that the person from whom I stole did not deserve what he had. I reason that what might look like an act of stealing was really an act of restorative justice. Similarly, we can’t not know that we must never take innocent human life, but the abortionist tries to convince himself that the unborn child wasn’t innocent, wasn’t human, or wasn’t really alive. Such excuses don’t erase the awareness of wrong; rather they suppress it by misapplication. Can the awareness of profound wrong be suppressed to the point of extinction? I don’t think so. For example, some abortionists who have written about their grisly trade admit that they have nightmares of their victims accusing them. This wouldn’t happen unless at some level, they knew that their lies were lies. Moreover, even in the case of the most hardened perpetrator of wrong, there can be such a thing as repentance and change of heart. Repentance is difficult, of course, because once we have done wrong, we “dig in” to evade the accusations of conscience – something that would hardly be necessary if conscience did not exist. But if there were no free will, repentance would not be merely difficult. It would be impossible. So far I have been speaking of those who perpetrate wrong, but conscience can also be distorted in the case of those who unjustly suffer it. Conviction of fault arouses in us an impulse to atone, to pay a price. Unfortunately, this impulse can arise not only when the fault is real, but also when it is imaginary. For example, a child who has been sexually abused may feel ashamed about the experience, telling himself that he was to blame for what happened to him. If he does, then the abuse may seem to him as though it were a deserved punishment. Or if people are constantly treated as inferiors, as in the cases you describe, they may come to think that they really are inferiors, and even that their inferiority is their fault. In this case they may believe that they deserve to be treated badly. Again, what drives submission to injustice is the misapplication of a real moral truth – in this case, the principle of desert. When people have been abused or mistreated, they often find it difficult to believe that they are made in the image of a loving God. Yet if only they can believe it, they rejoice to learn it. Moreover, although they may need help to understand that the things for which they blamed themselves were not really their fault, they experience this discovery as a liberation. So again, free will is vindicated – but its vindication comes through struggle and God’s grace. Perhaps these reflections help to explain what is going on when people seem to acquiesce in their oppression. Related:"The Revenge of Conscience"

|

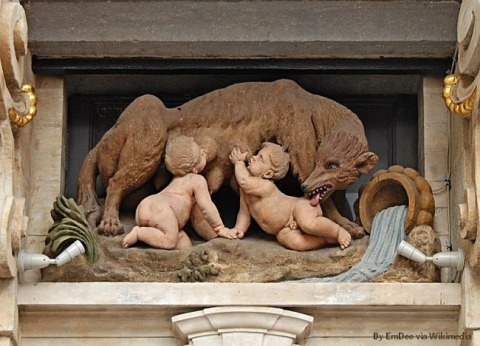

Children Raised by WolvesMonday, 10-30-2023

Query:Professor, does the fact that children raised by wolves cannot function in human society show that there is no human nature?

Reply:There are said to have been a few cases of this sort of thing, but no, you are working with a flawed definition of “nature.” As you are using the term, our nature is merely our innate behavior, fixed patterns of action which do not have to be learned. If you use the term that way, then just because there are so few such patterns – just because we might learn to act all sorts of ways, or fail to learn to act in the ways expected -- it seems that we haven’t any nature. However, our nature includes much more than innate behavior. It is better to think of it as a bundle of natural potentialities, distinct to human beings, which must unfold if we are to attain our full development and live well. In a properly human environment, these potentialities can fully unfold, but in a subhuman environment, they can’t. That is why children raised by wolves cannot function in human society. If there were no human nature, then children would flourish equally whether they grew up among humans, wolves, or ants. In ant society, they would thrive as though ants; in wolf society, as though wolves; and in human society, as humans. What we find is that in an ant society, they can’t function at all. In a wolf society, they can function but not thrive, for although they may be able, say, to catch rabbits, natural human potentialities such as language, rational inference, and the desire for truth and beauty have no chance to develop in them. Only in a human society can they flourish. Another way to think of this is that the natural habitat for human beings includes not only physical features of the environment, such as food, oxygen, dry land, and a certain range of temperature, but also social features of the environment, such as parents, friendship, conversation, and worship. Aristotle and Thomas Aquinas rightly say that man is “by nature” a social and political animal – “social” meaning that we live together and cooperate, “political” meaning that we provide for justice and take thought for the common good. When they say this, their claim isn’t that we form our communities by instinct, or even that we cannot live without them. Rather they mean that these communities are our natural habitat, so that without them, we cannot live well. A good life for wolves is not a good life for us.

|

Blessing IsraelThursday, 10-26-2023

Now the Lord said to Abram, “Go from your country and your kindred and your father’s house to the land that I will show you. And I will make of you a great nation, and I will bless you, and make your name great, so that you will be a blessing. I will bless those who bless you, and him who curses you I will curse; and by you all the families of the earth shall bless themselves.” Pray for the peace of Jerusalem! “May they prosper who love you! Peace be within your walls, and security within your towers!” For my brethren and companions’ sake I will say, “Peace be within you!” For the sake of the house of the Lord our God, I will seek your good. -- Genesis 12:1-3; Psalm 122:6-9

|