The Underground Thomist

Blog

The Use and Abuse of Brain ScienceMonday, 01-22-2024

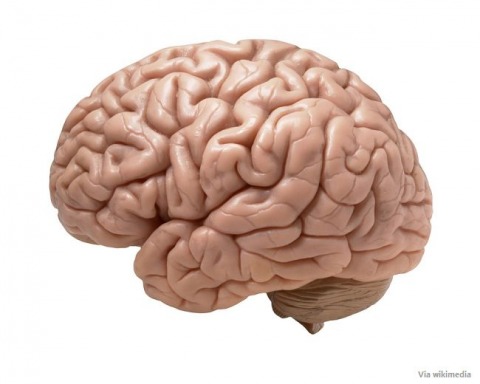

Neuroscience sometimes explains the how of a fact we shouldn't have needed neuroscientists to tell us. Often, though, the significance of the how is misunderstood. Example one. Lots of connections are still being made in the frontal lobes of the brain right through the ‘twenties. That’s not surprising. You don’t need brain science to understand that young people take a long time to develop mature judgment. Unfortunately, the fact that it takes time to become mature leads some people to the mistaken conclusion that young people shouldn’t take on any commitments or responsibilities until the process is complete. This ignores the fact that we develop mature judgment only by taking on and sticking to commitments and responsibilities. Besides, frontal lobes or no frontal lobes, good judgment doesn’t magically reach completion at age twenty-five or thirty. We are learning and relearning all our lives. Example two. A number of researchers have written that pornography rewires the brain. Of course it does. But we already knew, or should have known, that pornography is habit-forming, and this phrase merely tells us what the brain is doing when a habit is formed. All habits rewire the brain, just as all knowledge and belief do the same. Unfortunately, talk about brain wiring leads some people to the mistaken conclusion that habits are fates – that the brain makes people keep doing the same thing, so that they can’t reform their habits or get out of bad ruts. What a counsel of despair.

|

Is It Just Silly?Monday, 01-15-2024

Query:This will sound nuts -- then again, maybe not? I thought you could shine some light here if you have a moment or two. My daughter is now 18 and while she hasn’t taken to stripping, she’s got an OnlyFans subscription. Wonderful right? Thing is … its fetish based. It’s a strange world. You name it, truly. While she isn’t naked or stimulating herself or anything remotely close to what you would dub pornography … is this still wrong for her to do? Doesn’t it seem harmless and well ... a bit silly? If you have any insight at all that I can reason out please do send your input. If I talk to her about it, I’m likely to get the answer that fetishism isn’t the same as pornography.

Reply:Yes, this is certainly pornography. Sexual immorality is whatever deviates from the intended purposes of the sexual powers and feelings, which are given to us for the fruitful, personal love of husband and wife. Pornography is sexually immoral, because it consists of writing or images intended to cultivate and arouse disordered fascinations and desires. The immorality of the fetishistic variety of pornography lies in the fact that it attaches sexual desire to things, as well as to persons being used as things. It’s no accident that OnlyFans is used primarily by prostitutes for self-advertisement. Pornography and the habit of using it are not at all harmless or silly. Escape is certainly possible – but in the meantime, it subverts the imagination, reorients the desires, and alters the way people think. Those who are habituated to pornography tend to have emotional difficulty in normal relationships, because their emotions and attitudes become disarranged and they tend to develop unwholesome expectations of others. Over time, the things which first excited them lose the power to arouse, so they often turn to ever more extreme and unnatural fantasies in order to get that excitement back. We now find that among young men who use certain sorts of pornography, there has even been a rise in the desire that young women should submit to being choked. The bottom line is that you are right to be concerned, and you should not be embarrassed that your daughter’s interest in this kind of thing seems “off” to you. It is very much “off.” God bless your daughter and your guidance of her. Related:On the Meaning of Sex

|

Is It Blessed or Isn't It?Monday, 01-08-2024

I don’t like to write about things the hierarchy does badly, for fear of adding to the scandal by drawing attention to them. It hardly seems possible any longer for Fiducia Supplicans to receive more attention than it already has, so in a small way, let me break my rule. Once. I hope. Let us say this for the document: It explicitly says that it doesn’t change Church doctrine or approve irregular sexual relationships – which it couldn’t have done anyway. It also includes several explicit prohibitions which are supposed to make this clear: For example, blessings for people in irregular relationships must not in any way resemble marriage rituals. This helps too: According to what is called the hermeneutic of continuity, ambiguities of expression are always to be resolved in favor of established doctrine, not against it. Moreover, it was already possible, even before the promulgation of the document, to bless individuals in conditions of grave sin. A thief who cannot yet bring himself to turn away from theft cannot receive absolution, of course, but he may certainly ask for a blessing so that he might receive grace for the amendment of his life. Two partners in theft who come to the Church might even be individually blessed. Sam can be blessed, and Joe can be blessed. But their partnership cannot be blessed, because theft is its whole reason for being. It is the same for people in irregular sexual relationships. Any adulterer can ask to be blessed. In fact, each of a pair of adulterers can ask to be blessed. What they cannot ask is to be blessed as a couple, because this amounts to asking the Church to bless the adultery itself. The blessing is intended to offer the hope of grace for the remedy of sin, not to cheer it on. But priests were already able to bless people in a state of grave sin before Fiducia Supplicans. What then does the document allow them to do that they weren’t already able to do? If it doesn’t allow them to do anything new, then why was the document necessary? What was it for? One canonist suggested to me that Fiducia Supplicans was intended in part to rein in certain European bishops whose practices already go far beyond its explicit prohibitions. All things considered, however, is it likely that these renegades will take it as anything other than a green light? As, in fact, they are doing. What could have been expected from the promulgation of the document, other than the scandal and confusion which we are seeing already? This has been badly done. It isn’t “pastoral” to confuse people.

|

There Is Nothing ElseMonday, 01-01-2024

C.S. Lewis didn’t write this as a New Year’s reflection, but it works. The terrible thing, the almost impossible thing, is to hand over your whole self -- all your wishes and precautions -- to Christ. But it is far easier than what we are all trying to do instead. For what we are trying to do is to remain what we call "ourselves," to keep personal happiness as our great aim in life, and yet at the same time be "good." We are all trying to let our mind and heart go their own way -- centered on money or pleasure or ambition -- and hoping, in spite of this, to behave honestly and chastely and humbly. And that is exactly what Christ warned us you could not do. As He said, a thistle cannot produce figs. If I am a field that contains nothing but grass-seed, I cannot produce wheat. Cutting the grass may keep it short: But I shall still produce grass and no wheat. If I want to produce wheat, the change must go deeper than the surface. I must be ploughed up and re-sown. That is why the real problem of the Christian life comes where people do not usually look for it. It comes the very moment you wake up each morning. All your wishes and hopes for the day rush at you like wild animals. And the first job each morning consists simply in shoving them all back; in listening to that other voice, taking that other point of view, letting that other larger, stronger, quieter life come flowing in. And so on, all day. Standing back from all your natural fussings and frettings; coming in out of the wind. We can only do it for moments at first. But from those moments the new sort of life will be spreading through our system: because now we are letting Him work at the right part of us. It is the difference between paint, which is merely laid on the surface, and a dye or stain which soaks right through. He never talked vague, idealistic gas. When he said, "Be perfect," He meant it. He meant that we must go in for the full treatment. …. This is the whole of Christianity. There is nothing else. …. What we have been told is how we men can be drawn into Christ -- can become part of that wonderful present which the young Prince of the universe wants to offer to His Father -- that present which is Himself and therefore us in Him. It is the only thing we were made for. -- C.S. Lewis, Mere Christianity

|

Thus Did He EnterMonday, 12-25-2023

He had no earthly father; He abhorred to have one. The thought may not be suffered that He should have been the son of shame and guilt. He came by a new and living way; not, indeed, formed out of the ground, as Adam was at the first, lest He should miss the participation of our nature, but selecting and purifying unto Himself a tabernacle out of that which existed. As in the beginning, woman was formed out of man by Almighty power, so now, by a like mystery, but a reverse order, the new Adam was fashioned from the woman. He was, as had been foretold, the immaculate "seed of the woman," deriving His manhood from the substance of the Virgin Mary; as it is expressed in the articles of the Creed, "conceived by the Holy Ghost, born of the Virgin Mary." Thus the Son of God became the Son of Man; mortal, but not a sinner; heir of our infirmities, not of our guiltiness; the offspring of the old race, yet "the beginning of the" new "creation of God.” .... Thus did the Son of God enter this mortal world; and when He had reached man's estate, He began His ministry, preached the Gospel, chose His Apostles, suffered on the cross, died, and was buried, rose again and ascended on high, there to reign till the day when He comes again to judge the world. This is the All-gracious Mystery of the Incarnation, good to look into, good to adore. -- From a sermon by St. John Henry Newman on John 1:14

|

Happier Unhappy?Monday, 12-18-2023

Query:My students have just finished your book How and How Not to be Happy. They all really liked it. Several, some of them atheists, emailed me privately that the book helped them rethink their lives and values in a positive way. One told his mom to listen to it in the audio version. However, several did have questions and objections. In particular, what would you say about people who claim they don't experience the desire for complete happiness? And what would you say about people who seem to be perfectly happy but are atheists?

Reply:I’m glad they liked the book! Concerning their first question or objection, “What would you say about people who claim they don't experience the desire for complete happiness?” Let me ask in turn, if they don’t desire that kind of happiness, then what kind do they desire? Partial, flawed, and precarious happiness? I don’t believe it. Complete happiness means happiness so perfect that it leaves nothing further to be desired. Do they not desire that? They may not be pining away, saying “More, more, more!” But I don’t think they are pleading, “Okay, I’m happy enough now! Don’t make me any happier, I’m begging you!” Just like everyone else, people who speak as they do desire complete happiness -- but for fear of disappointment, they are trying not to desire it. They say they “don’t experience the desire for” complete happiness because they are trying to resign themselves to not having all that they could wish. They think they will be happier if they “settle.” Concerning the second question or objection, “What would you say about people who seem to be perfectly happy but are atheists?” -- I wouldn’t dream of denying that an atheist might have the partial, flawed, precarious happiness of this life. The closest formula for that is good character along with good fortune – as I put it in the book, virtue plus luck. But of course none of us has as much virtue as he needs, and the thing about luck is that it tends to run out. But really -- perfectly happy? If anyone did claim that he couldn’t be any happier than he already was, I would say that he didn’t have much imagination. I don’t even claim perfect happiness for theists in this life, because the happiness of the blessed will not be complete until we see God. They will be perfectly happy only when we are face to face with the very source of all meaning and happiness, who redeems even our present suffering. For now, we live in hope and longing. Maybe that’s a good note on which to end this Advent post. Related:How and How Not to Be Happy“God Rest Ye Merry, Melancholics”

|

BeerismMonday, 12-11-2023

Advertisements are well worth analyzing, since they make up so much of our education. Recently I passed by a billboard showing a photograph of people who had climbed ‘way up into the hills, and now, late in the day, were having a beer. The motto: “It isn't worth it unless you enjoy it.” I’ll bet the flacks who composed the slogan never expected anyone to disagree. Well, I have been known to have a beer with friends too (I like stout). But think about that motto. “It,” I suppose, means whatever one aims to achieve. Replace that vague word with an actual achievement. Your pick. It isn’t worth changing the baby’s diaper unless you enjoy it. It isn’t worth getting off drugs unless you enjoy it. It isn’t worth learning to read unless you enjoy it. It isn’t worth being kind to the old lady next door unless you enjoy it. It isn’t worth driving carefully unless you enjoy it. Hmm. How would the philosophy of beerism be expressed as a syllogism? Perhaps something like this. 1. Nothing is good except pleasure. 2. What you achieve doesn’t ever give you pleasure in itself. 3. Therefore it is pointless to achieve anything unless you are rewarded with some other unrelated pleasure, such as beer. But really: Lots of things are good besides pleasure. Difficult achievements usually do give you pleasure in themselves. It can be fun to enjoy a beer with friends when you have achieved something together, but it isn’t the beer that makes the achievement worth doing. And you could have had the beer without doing it. You aren’t celebrating the beer. You are enjoying the beer to celebrate the achievement.

|