The Underground Thomist

Blog

Religion and RiskMonday, 02-09-2026

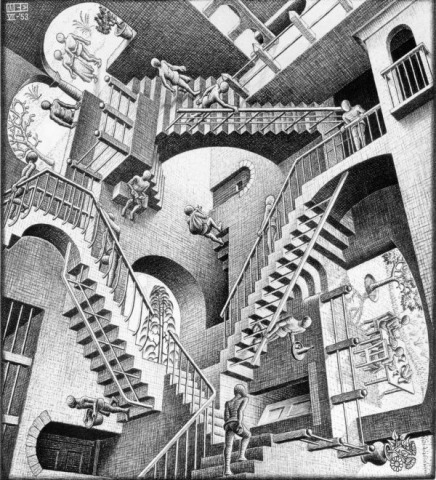

When my wife and I were still Protestant, but attracted to Catholicism, one of my issues was the Catholic practice of invoking the saints during prayer. In my boyhood I had been taught that this was little short of necromancy. However, I was just beginning to understand that Catholics don’t pray to the saints instead of praying to God, but in addition to doing so. For Catholics, this is an extension of the practice of all Christians to bear one another’s burdens and pray for each other. As we read in the Epistle of James, “The prayer of a righteous man has great power in its effects.” If I might ask a good and holy friend to pray for me, why not ask the mother of my Lord, who is even holier? Still, the practice was troubling, because, after all, couldn’t it happen that asking for the intercession of the saints might displace petitioning God Himself? In fact, I knew that it could happen. An Episcopalian lady I knew, herself a fallen-away Catholic, told me that she “felt closer” to Mary than to Jesus. This appalled me. As I came to learn, it also appalls the Catholic Church. Time and again, the Church emphasizes that wholesome Marian prayer is centered not on the Virgin herself, but on Christ. At the wedding feast in Cana, where we know Mary to have interceded with her son on behalf of friends who had asked for her help because no more wine was left, she didn’t say to the servants “Do whatever I tell you,” but “Do whatever He tells you.” When I learned to pray the Rosary, I found it helpful to think of Mary alongside me, helping me speak to her Son, speaking to Him along with me. A Catholic friend of mine helped me put this in perspective. “We want all the good stuff,” he said cheekily. Almost all the good stuff in the spiritual life is risky, but although the Church knows this, she views the risk differently that Protestants do. Traditional forms of Protestantism are risk-averse; their tendency is to view all spiritual risk as impermissible. But the Catholic view is that we should embrace all the good stuff while rejecting all the distortions. Don’t let the harmful things frighten you from enjoying the beneficial ones. Don’t let the false doctrines frighten you from embracing the true. From a Catholic point of view, that would be like cutting off one’s nose to spite one’s face. For example, to avoid unhealthy attitudes toward the dead, an Evangelical will decline to invoke the intercession of the saints at all. To avoid the temptation of drunkenness, a Baptist will use grape juice, not wine, to commemorate the sacrifice of Christ. To avoid the danger of polytheism, an old-fashioned Unitarian will reject the doctrine of the Trinity (though, curiously, modern Unitarians embrace every novel doctrine except the Trinity). Matters have gone so far that to avoid self-righteousness, some liberal Protestants decline to believe in God at all. By contrast, a Catholic asks the saints to pray for him, but in the same spirit in which he would ask his dearest and holiest friends to pray for him. He celebrates the conversion of the Eucharistic bread and wine into the Body and Blood of Christ, but he doesn’t believe in using wine to get drunk. He affirms the Three Persons because they really are Three Persons, but insists that they are only One Substance. And he earnestly believes in God, but instead of taking credit for his belief, he regards it as God’s gift. The temperamental difference between the two attitudes toward risk cuts deep in theology, and may be one of the reasons why putting an end to the schism with Protestantism is so difficult – it was certainly one of mine. But I think the difference runs through other aspects of life too. Consider the reluctance of most modern philosophers to think big. Instead they debate one tiny question at a time, but at interminable length. Granted, a person who thinks big may make big errors. But often even the tiny questions can’t be seen clearly, except in the light of a larger framework of thought. Their answers don’t make sense, apart from a background of answers to a host of other questions.

Note: The illustration to this post, “Don’t Cut Off Your Nose to Spite Your Face,” is from a book by the nineteenth-century Baptist preacher Charles H. Spurgeon. Never let it be said that I don’t acknowledge my debt to the Protestantism of my boyhood!

|

Pandemic of Lunacy Audiobook is #1 New Release!Friday, 02-06-2026

Gentle readers, I’m happy to announce that the audiobook of my new Pandemic of Lunacy: How to Think Clearly When Everyone Around You Seems Crazy, narrated by Tim Morgan, is Amazon’s #1 New Release in the category “Ethics and Morality Philosophy.” By the way, the audiobook is free if you sign up for a free trial from Audible, which is Amazon’s audiobook company. AND I've just learned that Creed and Culture, the publisher, is offering a 15% discount, good through the end of April, if you order the physical book through the Creed and Culture website and use the discount code PANDEMIC15. This is good only at the Creed and Culture website, not at Amazon or any other seller. Happy reading! Or listening! It may help you be sane in an increasingly lunatic world. P.S. If you read and like the book, please consider giving it a 5-star rating on Amazon, on Goodreads, or on both, and please tell a few friends about it. My publisher tells me that this is enormously important in bringing the book to the attention of its natural audience. The times they are a’changin’.

|

Political Marketing and the Real Reason Why People DrinkMonday, 02-02-2026

Political branding has now reached alcohol. On the right, we have Tears of the Left, which is a bourbon, and on the left, we have Fascist Tears, which is a vodka. Distilling the tears of the other side seems to be a draw. The Fascist Tears people bill themselves as being "women-owned, queer-led," and say part of their earnings helps “fund the resistance,” for example promoting abortion. So far as I can tell, the Tears of the Left people are only interested in making a little money and having a little fun. Curious to know whether these political potions are drinkable or just a way to cash in on political identity, I looked up a few reviews. Tears of the Left is much more well known. Most reviewers didn’t actually review the bourbon itself, but only vented their spleen against its politics. On the other hand, a Fascist Tears customer who did like its taste was especially pleased with the organic packaging, commenting “I will recycle the entire package.” I couldn’t help but smile when one spirits reviewer declared that although Tears of the Left marketing “thrives on antagonism” (he meant it makes fun of snowflakes), Fascist Tears marketing is “slightly less combative.” It’s hard to see how calling people fascists is less combative than calling them snowflakes, or how it isn’t antagonistic to say “We prefer our ICE crushed.” Was he not listening to himself? He added that political marketing ruins the experience of drinking together, because people do it -- wait for it -- for “diversity and inclusion.” So now we know why people really drink. You learn something every day.

|

Gospel SocialismMonday, 01-26-2026

One grows so weary of socialism being touted as the meaning of the Gospel. We see this in the secular world, of course. But we also see it in liberal Protestantism, and in certain Catholic circles too. This is especially awful because it is, in the literal sense, a heresy. It isn’t compassionate, and it has nothing to do with the Gospel. “Nothing to do with it? How can you say that?” To answer the question with a question: Can you tell me where the Gospel says it is wrong for anyone to have more or less than another? You can’t. The Gospel praises generosity and warns against the love of money, but what it condemns isn’t inequality of wealth per se, but exploiting and neglecting the poor – “the widow and the orphan,” who have no one to provide for them. Much of what government does today in the name of caring for the poor actually hurts them, but that is a story for another day. I was talking about inequality. The common assumption is that the poor are poor because other people are rich. Therefore, if no one was rich, no one would be poor. For example, a recent article in the Vatican newspaper L’Osservatore Romano laments that the wealth of those it considers super-rich “would be enough to eliminate extreme poverty in the world 26 times.” In case you’re wondering, that article is what lit the fuse for this post. Never mind whether the statistic is accurate. Does the author really suppose that simply transferring money from haves to have-nots will eliminate poverty? And does he really suppose that the poor in poor countries are the ones who would get the transferred money? How tempting to think so. It would be so easy! Just take it away from the rich people and give it all away! And since most of us aren’t rich (I’m not), thinking so makes us feel wonderful. But it’s false. If the rich use their wealth in a way that promotes economic development, then by doing so they help the poor. Needless to say, they might not use their wealth in that way, but in a capitalist economy, it is in their interest to do so. On the other hand, if the poor remain untrained and uneducated, with unstable marriages and family structures, without opportunities and incentives for employment, they will remain poor no matter how much money they are given. Moreover, if the governments of the poor countries fail to enforce the rule of law and operate as kleptocracies, whatever money you transfer to them will go to their kleptocrats, not to their poor. If you want to help the poor, here or abroad, help them overcome those burdens. I am unpleasantly reminded of a minister in Appalachia whom I heard railing against “global capitalism” as the cause of poverty, but had nothing at all to say about finishing school, working whenever possible, not using drugs, and not having children until getting married. Thank God he wasn’t typical. Doing those things wouldn’t end all poverty – remember the widow and the orphan! -- but it would end, or ameliorate, a lot of it. Do you think I am being mean? We need to rethink what it is to be mean. Suppose we take away all the wealth of a man who has started a business and built a factory paying good wages to 500 people, and we simply transfer all that money to low-income people. The poor who get the money will live well for a day, but the structural reasons for their poverty will be untouched. In the meantime, 500 hard-working people will be thrown out of their jobs. Who is being mean now? Yes, the starving man needs a meal. Feed him. But if you think he needs only a meal, you are a lazy thinker, self-serving, and desperately wrong. You are making yourself feel good about the poor on the backs of the poor. I am also weary, so weary, of seeing the look in the eyes of young men who see a job as just a temporary way to earn enough money to buy the next fix – who work for a few days or weeks, get stoned, and never show up again. And please don’t think I hear about such young men only from books. I am on first-name terms with some of them. I know their mamas. I also know some young men who by the grace of God broke out of that trap, got married, work every day, and are gradually building lives for their families. What is the real problem with inequality as such? None. Ask instead what is the real problem with extreme wealth. Very well, what is the problem with extreme wealth? Now comes the pivot, for there really are two problems with it. Not the ones you think. The first problem is that it risks grave spiritual harm to the rich person himself. He easily comes to think too well of himself, failing to recognize how he is needy before God. A genuinely poor person bears many burdens, but at least he is not exposed to that temptation. Blessed are the poor in spirit, for theirs is the kingdom of Heaven. The second problem is that extreme wealth buys great political influence, and no economic system has built-in incentives for political influence to be used for the common good. I mentioned that under capitalism, it is in the rich man’s material interest to use his wealth in a way that promotes economic development, because doing so profits him too. But unfortunately, it is also in his material interest to use it in a way that gains him privileges, subsidies, and other advantages from the government, at the expense of everyone else. Even Adam Smith, the famous proponent of the “invisible hand,” warned sternly against that. In fact, it is simply untrue that big business today exerts influence in favor of capitalism. If capitalism means free markets, it has been quite a long time since most capitalists believed in capitalism, which is why Wall Street is now more generally allied with the political Left. What we call capitalism today is more like socialism with outsourcing. Yet how naïve to think that unmixed, out-and-out socialism would cure that problem. In fact it would only replace a merely-influential big business class with a nearly-omnipotent bureaucratic and political class. Under the present system, big business must contend with the countervailing influence of many other social groups, and that’s good. Under socialism, though, the bureaucratic and political class would have the power to crush all competition. This has been tried. It hasn’t worked out well. Under socialism we are all equal. Equally poor.

|

Soapy WokeMonday, 01-19-2026

The determination of woke corporations to push their opinions in the faces of ordinary folks who don’t share them is just a part of a broader contempt for customers and clients who aren’t enough like the people in the executive suites. It’s a political thing, sure, but it’s even more a social class thing. They’re snobs. Cracker Barrel execs didn’t plaster their restaurants with BLM posters and LGBTQ flags, but even so they wanted Cracker Barrel to be the sort of restaurant in which they would like to eat, not the sort which their customers enjoy. Hollywood producers would rather make movies they would like to see, than the sort that moviegoing people want to. I'm sure that Bud Light execs were glad of their brand’s popularity, but they didn’t like the "fratty" people who bought it. Since I don’t watch daytime soap operas myself, it was a surprise to me to learn recently that this contemptuous attitude is in evidence even there. A woman I know who used to be fond of soaps explained to me that the traditional family crises and personal entanglements she loved seeing play out on the screen are vanishing from the shows she used to enjoy. Now, she lamented, everything in the plots is about business conspiracies and corporate backstabbing. “All these characters think about is their jobs.” Considering that soaps are watched mostly by women who may or may not work outside the home, but who care about other things more than their jobs if they do have them, it’s not surprising that the audience for soaps is shrinking. The writers – more likely, the people in the executive suites who give the writers their instructions – still want ratings, I suppose, but even more important to them is that the shows reflect their own preoccupations.

|

Like a Seed or SignetMonday, 01-12-2026

The classical writers often speak of laws being “impressed” into something or someone by some divine or human agent, as a seed is impressed into soil or the shape of the signet is impressed into wax. I think it is worthwhile to consider the various kinds of soils or waxes they had in mind. I am using the term “laws” broadly, not only for laws in the strict sense, addressed to rational beings, such as “Thou shalt not murder,” but also for patterns which are merely analogous to laws, such as the so called law of gravity. In either sense, laws are impressed -- Into inanimate things. Rocks fall to earth. Acorns aim at becoming oaks. They can’t help it. Into the nature of the passions. Although we can resist excessive passion or stir up deficient passion, we cannot change what the passions are in their very nature. However misguided our perceptions may be, we become angry only to protect perceived good against perceived bad, never the reverse. A dog growls when you take away his bone, not when you give him one. Into latent knowledge. Even before we are old enough to grasp abstractions, if mother asks us “How you you feel if she pinched you?”, we may grasp her point. Into developed knowledge. That seed of knowledge grows, as all seeds do, so that eventually we do come to understand such things as the Golden Rule. Into actual knowledge. It is one thing to know a rule, another to keep it in awareness. Into effective knowledge, which is also called wisdom. It is one thing to keep a rule in awareness, still another to grasp how to apply it. Into innate habit. An infant will often take the teething biscuit out of his mouth and offer it to those watching, just because the giving impulse strikes him. This habit is not true generosity, but it can be shaped and trained. Into acquired habit. Even if we are fearful, if we resist our fear often enough, the act may become habitual. A person with such a habit is called brave. Into acquired virtue. We must take into ourselves what to be brave about, how brave to be, on what occasions, toward what people, and for what reasons. A person with such a habit is properly called not merely brave but courageous. Into infused virtue. Through cooperation with the grace of God, our ordinary virtues may be healed and uplifted to heights we cannot attain by ourselves. Consider the martyrs. Into habitually infused virtue. Through the habit of cooperation with grace, we may acquire a sort of habit of receiving it. Contrast a person rowing against a strong current with a person with the wind in his sails.

|

New Interview about my New BookMonday, 01-05-2026

My dear readers, (Doesn’t that salutation make me sound like a Nigerian prince? But then I would have said dearest.) My new book Pandemic of Lunacy: How to Think Clearly When Everyone Around You Seems Crazy is coming out on February 3. Right after Christmas, I was interviewed about it by Tom Loarie of TheMentorsRadio.com. His popular podcast deals with all sorts of things at the intersection of life and work, featuring conversations with CEO and other prominent figures in the business world – with a few exceptions like me, of course. He had a lot of thoughtful questions, and I think you’ll find the interview interesting. We talked less about the content of the book than about what prompted me to write it. Something strange is happening to us: Why does our society seem to be going crazy? (As another reader remarked to me: “Why do you say seems to?) You can find the interview linked on my Talks Page, if you would rather go straight to the audio you can do that too, and if you would like to find out more about Tom Loarie’s podcast series, you can go his own website, TheMentorsRadio.com.

|