For a very ancient image of the right relation among the powers of the soul, picture a rider, a horse, and a lion. The rider sits tall in command; the horse swiftly and obediently carries him to his destination; and the lion assists him to overcome his obstacles and foes. Though horse and lion are on good terms not only with the man but also with each other, the lion is the nobler of the two beasts, urging on the horse in its exertions.

The man is not the soul per se, but reason, which is the soul’s highest power – the one through which the “I” most clearly speaks. The horse is the soul’s power to stretch out toward what seems delightful. The lion signifies the ardor or fierceness by which it stretches out toward same goods, viewed as arduous or difficult of accomplishment. Reason is shown in the saddle because of his calling to be their master. His rule is a royal rather than despotical, because the subordinate powers are able to resist. Yet even someone who scarcely understands what royalty means may grasp that unruly things must be brought under royal rule and law.

So much for the image in miniature. Now by opening it up into three different scenes, we get a glimpse of how such royal rule might be accomplished. In each scene, the man, the lion, and the horse stand in a different relationship.

Scene one unfolds at night. A muddy road stretches out toward the eastern horizon, but the road is hard to see. In this scene the horse is not a horse, but a shaggy-eared ass, and the lion is not a lion, but a scrawny wildcat. In his right hand, the man is holding the ass’s reins, though he doesn’t seem to know what to do with them. In his left, he is holding a whip. The ass continually brays, “You had better feed me,” and whenever it does, the man obeys. All down the roadside he walks in search of things for the ass to eat. Every now and then, he thinks it might be more dignified to ride in the saddle, but whenever he tries to climb into it, the ass rears and plunges to dismount him, then drags him around by the reins. As he is being dragged, the wildcat bites him, yowling “Do as the ass says!” Sometimes he strikes back at the two animals with his whip. The ass, knowing that his mood will pass, sits down on its rump to wait him out. The wildcat cringes, but it is only cowed, not tamed. Eyes flaming with anger, it waits its chance to bite again. If anyone asks this poor man what he is doing, he says, “I’m pursuing my happiness.”

In scene two, the man is still there, but the ass has become a brawny mule, and the wildcat a starving leopard. This time the man has some control over his animals, but his command is uncertain because they are more powerful than he is. Although he is seated on the mule’s back, trying to direct it down the highway, they are making little progress. Sometimes the mule turns off the road into pasture. At other times it stays on the road and perhaps even gallops, but as often as not, it runs in the wrong direction. Though the man uses whip, reins, and spurs, it detests being checked; twisting its head around to face him, it shows its blocky teeth and brays, “I haven’t yet lost my strength. You had better fear me.” But then the leopard snarls, punishing the mule by sinking its fangs into its flank. As the mule reverts to sullen obedience, the leopard gives the man dark looks and mutters, “I don’t know why I should be helping you.” The sun has risen, so the man can see the road, but he is ashamed to be seen because he looks so ridiculous. If anyone asks this poor man what he is doing, he says “I’m trying to be good.”

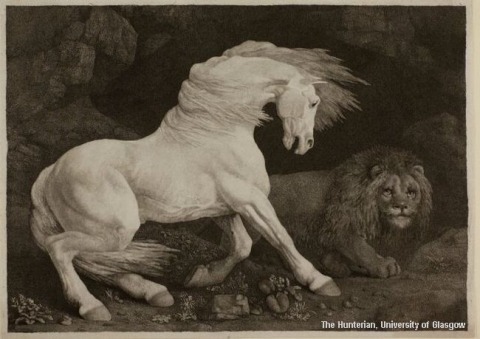

In the final scene, the man is clad in knight’s armor, laughing and singing fighting songs. The mule has turned into a white stallion, and the leopard into a tawny, noble lion. Thunderously purring, the great cat sidles up to the knight’s knee and rumbles, “Where is the enemy? Command me!” Snorting and rearing, the stallion neighs, “Where may I carry you? Let me run!” The man guides the stallion with nothing but his knees and a few quiet words. In place of the whip, he carries a sword for making swift work of foes and barriers. Sometimes at a canter, sometimes at a gallop, the three of them head down the high road, straight toward the sun. Although that great orb is so bright that it ought to blind them, and so blazing that it ought to consume them, instead it gets into them like molten gold. If anyone asks the man where he is going, he answers “Toward joy.”

As these three scenes tell the story, the desire for the delectable good and the desire for the arduous good are made to be ruled by intelligence, but desire can resist intelligence instead of obeying it. The loyalty of ardor in this contest is uncertain – on one hand it may side with the other appetite, but on the other hand it may side with intelligence, for as we know, a man can become just as angry and ashamed with himself for trying to exert self-control as for not exerting it. Even when ardor does side with intelligence, it may do so resentfully, like a slave, rather than loyally, like a servant.

For all these reasons, the first efforts of someone attempting purity and self-command may seem ridiculous, not only to others but also to him. Nonetheless there is something lofty about these efforts, for it is better to try and fail than not to try. Though it may seem at times as though the whole matter were nothing but a mass of difficult rules, the rules themselves are made for a great and beautiful reason, for removal of the obstacles that keep the soul from riding swiftly to the sun and becoming as resplendent as it is.

A word against overstatement. Very few of us in this life seem much like molten gold. Even those who reject the first scene are more like the second than they would wish. Progress down the road is measured not in miles but in inches. Even so, it is measurable. Our efforts become less and less ridiculous; we begin to catch the golden scent of the burning sun even when still far from it. Siegeworks that once would have stopped us, we begin to be able to scale. About those mightier barriers that still exceed our strength, there are rumors of help from the Emperor; but these reach our ears not from natural law, but from Divine.