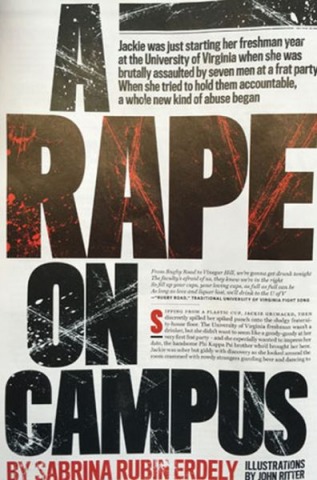

This month, after a scathing investigation by Steve Coll, Sheila Coronel, and Derek Kravitz of the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism, Rolling Stone magazine officially retracted its November story about a supposed gang rape at a University of Virginia fraternity house. Managing editor Will Dana writes, “We would like to apologize to our readers and to all of those who were damaged by our story and the ensuing fallout, including members of the Phi Kappa Psi fraternity and UVA administrators and students.”

The only mystery here is why Rolling Stone waited five months. As Dana admits, critics had questioned the journalistic failings of the story within days of its publication. We now know that although the magazine’s “fact checker” had interviewed “Jackie,” the young woman who made the allegation, at length, the staff made no attempt to contact those whom she accused. In fact, they couldn’t have, because she refused to provide the name of the alleged leader of the alleged assault. In other words, there was no fact checking at all. But the reporter, the editors, and the fact-checker-who-didn’t-check-facts “believed firmly that Jackie's account was reliable,” so they reported it as fact.

Then again, perhaps the long delay isn’t so mysterious. The psychology of this sort of journalism is exhibited in a December essay titled “Why We Believed Jackie’s Rape Story,” published in the UVA student newspaper, the Cavalier Daily, by Julia Horowitz, who was then its assistant managing editor and has since been elected as its editor-in-chief. “[I]t is becoming increasingly clear that the story ... has some major, major holes,” she said at that time. “Ultimately, though, from where I sit in Charlottesville, to let fact checking define the narrative would be a huge mistake.”

People accustomed to speaking frankly may be baffled by the meaning of that statement. Let’s decode it. In plain English, Ms. Horowitz is saying that journalists shouldn’t base their stories on the facts; they should trim the facts to fit the stories they have already decided to tell. For her, there would have been no need to find out whether the allegations of gang rape were true, because reporting them as true made women feel “comfortable sharing their stories.” The important thing isn’t whether a story is accurate, but whether it promotes her preferred view of reality.

But Ms. Horowitz is wrong. Sexual assault is a filthy crime; so is false accusation. We don’t have to be cavalier about the possibility of lying just to prove how serious we are about rape. Truth is not served by indifference as to which things are true.

Tomorrow: Getting the Bugs Out of Humbug