Surveys consistently show that overwhelmingly majorities of journalists identify themselves as liberal or progressive (pretty much like university professors). In theory, journalists could be liberal and still treat conservatives fairly. Conservatives say that they don’t. Liberals respond by citing supposedly neutral studies and “fact checks” showing that they do. But studies of bias are married by gross biases about what counts as bias.

Another reason for denying bias is that it often lurks in subtle things that make big differences. For example, how do journalists compare numbers? Suppose the average incomes of groups A and B are $50,000 and $100,000 in one year, and $55,000 and $106,000 in the following year. Comparing dollar amounts, the difference between the wealthier and poorer groups has increased from $50,000 to $51,000. But comparing ratios, the wealthier group started out making twice as much as the poorer group, but ended making only about 1.9 times as much. So in dollar terms the poor are falling further behind, but in percentage terms they are catching up. The safe thing would be to report the raw numbers along with both measures of difference, but does that often happen?

The third and most interesting reason why liberal bias may be denied is that different biases may obscure each other. Leftism is far from being the only common bias in the media.

For example, in a paradoxical sense, journalists tend to be pro-presidency. Most are in love with the institution of the Presidency, even though they may detest the fellow who inhabits it at any given moment. No other office in the government is so made for the media. It's unique, it's powerful, it's glamorous, it contains within itself all sorts of possibilities for tragedy and triumph, agony and ecstasy.

News people also tend to be pro-politics. Political developments are treated as big news; developments in marriage, family, religion, and society are slighted. One reason may be that political changes can happen more quickly. But another is that the liberal views of most journalists lead them to consider government more important.

Media folk tend to be pro-passion even if they adopt a cool style of reportage. During one of Mr. Obama’s presidential campaigns, a female supporter standing at the back of the stage shed tears as the candidate delivered his speech. Brit Hume, not at all an excitable man, and one of the rare network commentators who is conservative, was moved to offer the awed remark that she showed what politics is all about. Contrast the Founders, who considered passion deadly to republican politics, built features into the Constitution to defuse it, and hoped that the people would be calm.

Reporters like activity. Whether a politician is liberal or conservative, they like him to do things. Not only does activity make good press, but it ties in with at least a part of liberal ideology about the proper role of government.

They like conflict. It’s boring to report that people are getting along, but it’s fun to write about people scratching each other’s eyes out. If there isn’t any conflict to report, journalists try to invent it. “Mr. President, what would you do if your subordinate refused to obey your orders?” “He’s not going to do that.” “But Mr. President, what if he did?”

Almost all of them are hostile to expressions of faith. Most view faith as a matter of feelings with no basis in reason, even if the religion under examination views faith and reason as allies, as Catholicism does. Most place all strong belief in the same basket, for example calling strong conviction “fundamentalist” whether it is Christian, Jewish, Muslim, or Hindu. Most connect strong belief with intolerance, even if, like St. Hilary of Poitiers, one of the things the believer believes is that God does not desire an unwilling worship or a forced repentance. Most also assume that faith is hypocritical – “he doesn’t really believe that” -- while faithlessness is sincere. If we use the term “religion” for a person’s unconditional loyalties, then the anti-religious journalist is religious too, but he doesn’t tell you – and may not know -- what god he himself worships.

They glory in scandal. Virtue may be more interesting to live, but vice is more interesting to watch. Even if the fellow bleeding in the water is one of theirs, journalists find it difficult to resist joining the sharks, although sometimes, if the stakes are high enough, they will do it. In fact, anyone who shows conspicuous marks of virtue – or even of thinking it important -- is bound to become a special target. This is not entirely bad; if moral character is important, then when a statesman does something deplorable, we need to know about it. On the other hand, excessive coverage of real, accused, hypothetical, and even imaginary crookedness, is not only the product of cynicism but also produces it. It makes us doubtful about the very possibility of good character and blasé about its importance.

They love disaster. As Joseph Epstein has remarked, “In journalism, they used to say ‘if it bleeds, it leads’; nowadays the saying is ‘if it weeps, it keeps.’” Grief is more interesting than happiness. Catastrophes and human sorrows sell the news. It is in the interests of the news industry to make most trouble seem worse than it is. Someone tends to be blamed for everything bad that occurs. Who gets the blame is another question, and may have little to do with who, if anyone, is responsible.

Although they are still called reporters, more and more they prefer interpreting facts to reporting them – even if the facts are imaginary. Sometimes the interpretation is reported as a fact, and the fact is not reported at all. This begins with slanted headlines, which are all that some readers read. As columnist Holman Jenkins points out, “reporters are actually praised for ‘advancing the narrative’ – e.g., finding ‘facts’ to support a desired story line.”

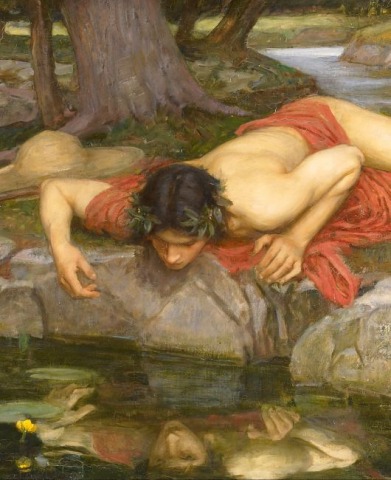

Finally, there is the narcissus syndrome, for journalists tend to be fascinated with themselves. One aspect of this is that they are unfamiliar with people who are not like themselves, and often contemptuous of them – although there is some evidence that in general, conservatives understand liberals better than liberals understand conservatives.* Another aspect is that journalists tend to find themselves eminently worthy of attention. Reporters report the opinions of reporters. Headlines are composed about headlines. The dumping of a network news anchor is treated as having the same news value as the resignation of a prime minister whose government has collapsed.

What about my own biases? I am putting these observations in plain sight so that you can decide for yourself whether I am wearing my spectacles crooked. Here is how it seems to me; compare it with how it seems to you.

* See: Character May Be Destiny, Personality Isn’t