Query:

I write about one of your presidents, Abraham Lincoln. Since I studied the man in the United States, he has become my favorite historical character, barring Christ and some of the saints.

Different scholars say different things about Lincoln’s faith. He believed in God, and he read enough scripture to have memorized lots of it. On the other hand he declined to affiliate with any Christian body, and some suggest that he did not believe in an afterlife. I hope he is an uncanonized saint. I place this hope in what seemed to be an authentic conversion when his son Willie died in 1862.

I don't know if I am mistaken in admiring a man so hard to pin down. We are supposed to revere virtue, and I see so much in him. He is to me the high water mark of a statesman, up there with St. Thomas More. Here is the kicker: Should I feel this way about Lincoln even though he didn't exhibit in a clear way the virtue of faith?

It seems to me that that he embodied the theological virtues far better than some supposedly Christian figures. Is this even possible? I would like to think that if he had been properly catechized, he would have assented, but how could I know? I would love whatever insights you may have on the matter.

Reply:

These few thoughts of mine on implicit faith might interest you. But about your question --

It’s true that Lincoln didn’t join any church. Yet we ask God in the Mass, “Remember … all who seek you with a sincere heart. Remember those who have died in the peace of Christ and all the dead whose faith is known to you alone.” At least Lincoln seems to have sought God. We may hope that he was one of those whose faith was known to God alone. If he really did seek God with all his heart, then we can be sure that he found Him, for we are promised that those who seek will find.

We just can’t know a person’s inward state. Some who seem virtuous are full of secret corruption, and some whom we might not consider exemplars are striving for God with all their hearts. Yet if God wants us to hope for the salvation of each person, then two things follow: Not only that we should never feel that we are doing something wrong when we do hope for it, but also that we should never feel that we are doing something wrong when we hope that the outward signs of virtue we see in others may be genuine. That would certainly include Lincoln.

As you know, the Tradition distinguishes between the ordinary virtues, typified by prudence, justice, temperance, and courage, which we can acquire by human effort, and the theological virtues, typified by faith, hope and charity, which we require the infusion of divine grace. But although the cardinal virtues are insufficient for salvation, they are not for that reason not virtues, and should still be admired. We might add that whether or not he possessed them, Lincoln plainly believed in the theological virtues. He said that we should accept by reason everything in Scripture that we can, and the rest by faith. In his Second Inaugural Address, he also preaches both hope – not just worldly hope, I think, but hope for God’s mercy – and charity for all.

Moreover, the Address reflects profound understanding of our need for that mercy. When he writes, “the judgments of the Lord are true and righteous altogether,” he is quoting from Psalm 19, which goes on to plead, “Who can understand his errors? Cleanse thou me from secret faults.” To plead in this way is to concede that we cannot cleanse ourselves. We need to be forgiven and to be purified – two things -- and for both of them we depend utterly on God. That is the crux of the matter, which is another way of saying that it is the Cross of the matter.

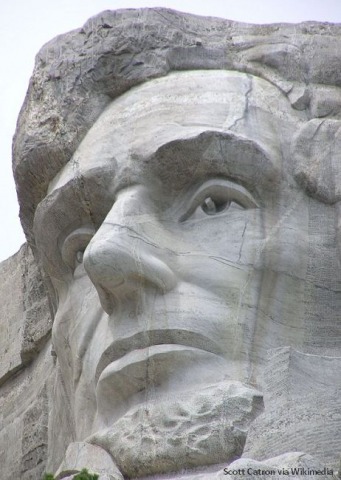

Despite Lincoln’s profound opposition to slavery, the mob in my country destroys his monuments and pillories his reputation, just because there was slavery. In this world, infamy may be a fate of vice, but defamation is the fate of virtue, and that too is a lesson of the Cross.