The Underground Thomist

Blog

Woke as PradaMonday, 03-02-2026

Wokeness is often thought to be a form of virtue signalling. This is subtly wrong, for it is more often a kind of status signalling. The wokist wants to be seen as belonging to “the right kind of people.” He drapes himself with wokeness the same way that in another day and age people paraded their memberships in prestigious clubs, or that today they flaunt the brands and styles of shoes and clothing that they wear. If ethics comes into the matter at all, it comes in not via the thought “I would never do that,” but via the thought “I’m not the kind of person who would do that.” You know, the deplorables. I am not suggesting that such a person is aware of his cravimg for status. Very few people are fully aware of their own motives. In a society which professes to believe in equality, and pretends to despise snobbery, it is hard for a snob who knows he is a snob to think well of himself; therefore he has to convince himself that he isn’t a snob. With its faux concern for The People (most of whom have no interest whatsoever in the cause of woke), wokeness is a convenient way to do that. My very expensive jeans must have holes in them.

|

MORE New StuffMonday, 02-23-2026

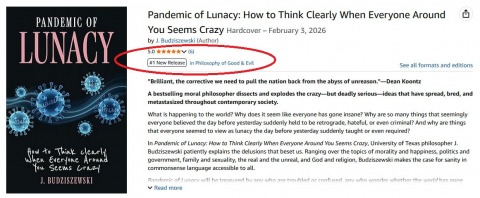

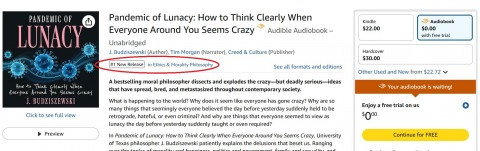

MORE new stuff! Last Monday I posted links to some new articles of mine and interviews about my new book Pandemic of Lunacy: How to Think Clearly When Everyone Around You Seems Crazy. I promised more items this week, and you’ll find them below. But first some more news: As of Tuesday the 17th, the book was Amazon’s #1 New Release in Philosophy of Good and Evil. Wednesday morning, the 18th, that flag had been replaced by #1 Best Seller in LGBTQ+ Political Issues (that was a surprise). Later on Wednesday, the flag was replaced with #1 New Release in Philosophy of Ethics & Morality. Apparently, when there is more than one flag, the flags rotate.

New Articles:“Why Scientists, Scholars, and Experts Are Not – and Cannot Be – Neutral Authorities” (Real Clear Books) “Open Our Eyes: A Vaccine for the Pandemic of Lunacy” (Touchstone, cover story) “There Is Only One Human Nature” (National Catholic Register) “No, Virginia, Each Person Does Not Have His Own Reality” (American Spectator)

New Interview:The Voice of Reason Podcast with Andy Hooser. Interview begins at 19:48.

And ...The Table of Contents and Introduction to the book are right here. You can get a 15% discount from the publisher’s website through the end of April by using the discount code PANDEMIC15. This discount code doesn’t work with Amazon, but you can get the Audiobook free from Amazon if you sign up for a free trial. If you read and like the book, I hope you will consider giving it a 5-star review on Amazon.

|

Pandemic of Lunacy Now Rated #1 New Release in Two More Amazon CategoriesWednesday, 02-18-2026

My wonderful readers will want to know that my new book Pandemic of Lunacy: How to Think Clearly When Everyone Around You Seems Crazy is still climbing in the ratings. I posted on February 6th that it was Amazon’s #1 New Release in its subject area in the audiobook category -- and it’s now the #1 New Release in Philosophy of Good and Evil, and #3 in Philosophy of Ethics and Morality, in the hardcover and kindle categories as well. The Philosophy of Good and Evil rating is shown in the image above, and you can see the #3 rating in Philosophy of Ethics and Morality by going to this Amazon page. I suspect that the rating of new releases is based largely on customer reviews, so if you read the book and like it, I hope you will consider giving it a 5-star rating on Amazon. Six are up already. And if you want to get a 15% discount, you can go to the publisher’s website and use the discount code PANDEMIC15. This is good through the end of April. God bless you all. We all need to avoid being infected with the virus of lunatic thinking, and I’m so glad that so many of you are enjoying the book. For your reading and listening pleasure, I’ll have a set of new articles and interviews related to the book in this coming Monday’s post.

|

New Stuff!Monday, 02-16-2026

New stuff! Here are some new articles of mine, as well as one of the first interviews about my new book Pandemic of Lunacy: How to Think Clearly When Everyone Around You Seems Crazy. More next week! By the way, the Table of Contents and Introduction to the book are right here. You can get a 15% discount from the publisher’s website through the end of April by using the discount code PANDEMIC15. The discount code doesn’t work with Amazon, but you can get the audiobook free from Amazon if you sign up for a free trial.

New articles:“Why Is There So Much Lying in Politics Today?” (Real Clear Politics) “Are We Just Animals? A Tempting Delusion” (Science and Culture) “Speaking of Reality: Men Are Not Women” (Daily Signal)

New interview:The Spectacle Podcast with Melissa Mackenzie and Scott McKay

|

Religion and RiskMonday, 02-09-2026

When my wife and I were still Protestant, but attracted to Catholicism, one of my issues was the Catholic practice of invoking the saints during prayer. In my boyhood I had been taught that this was little short of necromancy. However, I was just beginning to understand that Catholics don’t pray to the saints instead of praying to God, but in addition to doing so. For Catholics, this is an extension of the practice of all Christians to bear one another’s burdens and pray for each other. As we read in the Epistle of James, “The prayer of a righteous man has great power in its effects.” If I might ask a good and holy friend to pray for me, why not ask the mother of my Lord, who is even holier? Still, the practice was troubling, because, after all, couldn’t it happen that asking for the intercession of the saints might displace petitioning God Himself? In fact, I knew that it could happen. An Episcopalian lady I knew, herself a fallen-away Catholic, told me that she “felt closer” to Mary than to Jesus. This appalled me. As I came to learn, it also appalls the Catholic Church. Time and again, the Church emphasizes that wholesome Marian prayer is centered not on the Virgin herself, but on Christ. At the wedding feast in Cana, where we know Mary to have interceded with her son on behalf of friends who had asked for her help because no more wine was left, she didn’t say to the servants “Do whatever I tell you,” but “Do whatever He tells you.” When I learned to pray the Rosary, I found it helpful to think of Mary alongside me, helping me speak to her Son, speaking to Him along with me. A Catholic friend of mine helped me put this in perspective. “We want all the good stuff,” he said cheekily. Almost all the good stuff in the spiritual life is risky, but although the Church knows this, she views the risk differently that Protestants do. Traditional forms of Protestantism are risk-averse; their tendency is to view all spiritual risk as impermissible. But the Catholic view is that we should embrace all the good stuff while rejecting all the distortions. Don’t let the harmful things frighten you from enjoying the beneficial ones. Don’t let the false doctrines frighten you from embracing the true. From a Catholic point of view, that would be like cutting off one’s nose to spite one’s face. For example, to avoid unhealthy attitudes toward the dead, an Evangelical will decline to invoke the intercession of the saints at all. To avoid the temptation of drunkenness, a Baptist will use grape juice, not wine, to commemorate the sacrifice of Christ. To avoid the danger of polytheism, an old-fashioned Unitarian will reject the doctrine of the Trinity (though, curiously, modern Unitarians embrace every novel doctrine except the Trinity). Matters have gone so far that to avoid self-righteousness, some liberal Protestants decline to believe in God at all. By contrast, a Catholic asks the saints to pray for him, but in the same spirit in which he would ask his dearest and holiest friends to pray for him. He celebrates the conversion of the Eucharistic bread and wine into the Body and Blood of Christ, but he doesn’t believe in using wine to get drunk. He affirms the Three Persons because they really are Three Persons, but insists that they are only One Substance. And he earnestly believes in God, but instead of taking credit for his belief, he regards it as God’s gift. The temperamental difference between the two attitudes toward risk cuts deep in theology, and may be one of the reasons why putting an end to the schism with Protestantism is so difficult – it was certainly one of mine. But I think the difference runs through other aspects of life too. Consider the reluctance of most modern philosophers to think big. Instead they debate one tiny question at a time, but at interminable length. Granted, a person who thinks big may make big errors. But often even the tiny questions can’t be seen clearly, except in the light of a larger framework of thought. Their answers don’t make sense, apart from a background of answers to a host of other questions.

Note: The illustration to this post, “Don’t Cut Off Your Nose to Spite Your Face,” is from a book by the nineteenth-century Baptist preacher Charles H. Spurgeon. Never let it be said that I don’t acknowledge my debt to the Protestantism of my boyhood!

|

Pandemic of Lunacy Audiobook is #1 New Release!Friday, 02-06-2026

Gentle readers, I’m happy to announce that the audiobook of my new Pandemic of Lunacy: How to Think Clearly When Everyone Around You Seems Crazy, narrated by Tim Morgan, is Amazon’s #1 New Release in the category “Ethics and Morality Philosophy.” By the way, the audiobook is free if you sign up for a free trial from Audible, which is Amazon’s audiobook company. AND I've just learned that Creed and Culture, the publisher, is offering a 15% discount, good through the end of April, if you order the physical book through the Creed and Culture website and use the discount code PANDEMIC15. This is good only at the Creed and Culture website, not at Amazon or any other seller. Happy reading! Or listening! It may help you be sane in an increasingly lunatic world. P.S. If you read and like the book, please consider giving it a 5-star rating on Amazon, on Goodreads, or on both, and please tell a few friends about it. My publisher tells me that this is enormously important in bringing the book to the attention of its natural audience. The times they are a’changin’.

|

Political Marketing and the Real Reason Why People DrinkMonday, 02-02-2026

Political branding has now reached alcohol. On the right, we have Tears of the Left, which is a bourbon, and on the left, we have Fascist Tears, which is a vodka. Distilling the tears of the other side seems to be a draw. The Fascist Tears people bill themselves as being "women-owned, queer-led," and say part of their earnings helps “fund the resistance,” for example promoting abortion. So far as I can tell, the Tears of the Left people are only interested in making a little money and having a little fun. Curious to know whether these political potions are drinkable or just a way to cash in on political identity, I looked up a few reviews. Tears of the Left is much more well known. Most reviewers didn’t actually review the bourbon itself, but only vented their spleen against its politics. On the other hand, a Fascist Tears customer who did like its taste was especially pleased with the organic packaging, commenting “I will recycle the entire package.” I couldn’t help but smile when one spirits reviewer declared that although Tears of the Left marketing “thrives on antagonism” (he meant it makes fun of snowflakes), Fascist Tears marketing is “slightly less combative.” It’s hard to see how calling people fascists is less combative than calling them snowflakes, or how it isn’t antagonistic to say “We prefer our ICE crushed.” Was he not listening to himself? He added that political marketing ruins the experience of drinking together, because people do it -- wait for it -- for “diversity and inclusion.” So now we know why people really drink. You learn something every day.

|